Injuries and deaths as a result of road collisions impose huge costs on our society, both on the people directly involved and an others more indirectly affected. While everyone will react differently to being in a road collision, we can try to quantify the average social and economic impacts in order to get at the overall cost to society as a whole and hopefully provide a further incentive for change.

The Department for Transport estimates the total cost of a road fatality to be around £1.7 million, of a serious casualty around £190,000, and of a slight casualty around £15,000. These are arrived at using the 'willingness to pay' economic method, and are meant to take into account the 'human costs' of suffering and grief, lost economic output due to injury or death and the costs of medical treatment.

Using these figures DfT estimates the total cost of reported road casualties in Britain in 2001 to be around £15.6 billion, and the total cost including unreported casualties to be up to around £34.8 billion.

Using the same average costs, Transport for London estimates the total cost of reported road casualties in London in 2011 to be around £2.35 billion. Since TfL also provide data on the location, mode and severity of each casualty in London in 2012, we can use the same figures to see how these costs vary from borough to borough and mode to mode.

The chart below shows the estimated total social and economic cost of reported road casualties in 2012 by borough and the casualty's mode of transport, using DfT's averages. There's a table with the same figures below the fold.

There are huge variations between boroughs in terms of both the scale and the composition of the costs associated with road casualties. The total cost in lowest in Kingston at around £27 million, and highest in Westminster at around £128 million. In Outer London boroughs car occupants account for a higher proportion of casualties and therefore of costs, while in some Inner London boroughs pedestrians and cyclists account for over half the costs, reaching 58% of the total in Westminster and 69% in the City of London. Across all boroughs the total costs by mode come to £523m for pedestrians, £345m for cyclists, £674m for car occupants and £518m for other modes (motorcycles, buses, taxis, goods vehicles, etc).

It's worth emphasising that these figures are bound to be an underestimate. Not only do they cover only reported casualties and excluse those that go unreported, but they arguably don't capture the full range of costs. Road danger results in 'avertive' behaviour, where people go out of their way to avoid particular danger-spots or choose to take modes of transport which are safer but slower or more expensive. These costs are very difficult to quantify and so they aren't included in the DfT figures.

Also, the average costs per casualty are likely to be higher in London than in other parts of the country, given the higher wages in London and therefore higher costs of lost output and higher 'willingness to pay' to avoid casualties.

It may sound callous to talk about road casualties in terms of money but this is really just a way to try and quantify the non-monetary costs in a rigorous way. And I think these figures could be a useful tool for campaigners too. Some boroughs don't seem to attach enough importance to road safety (or road danger reduction, if you prefer), but if the government were to levy fines on them in proportion to these costs I think it would concentrate minds pretty rapidly.

Showing posts with label transport. Show all posts

Showing posts with label transport. Show all posts

Monday, 29 July 2013

Wednesday, 17 July 2013

London shows you don't need new roads to tackle congestion

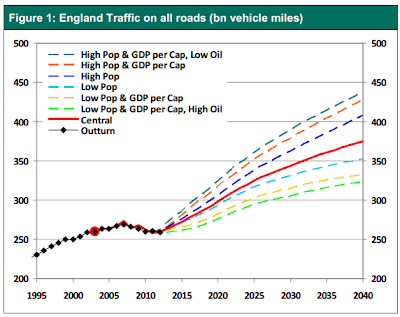

The Department for Transport has released traffic forecasts which, like Department for Transport forecasts always do, predict huge increases in traffic over the coming decades.

The first thing to say about these is that if they are anything like as accurate as previous DfT forecasts, the actual trend in traffic will be much lower.

The other interesting thing is the section where DfT's forecasters try to explain why they got the London traffic trend so completely wrong (they forecast a drop of 1.5% between 2003 and 2010 but the actual drop was 7.8%, despite the population growing faster than anyone thought). They say:

So why are the government doing the opposite of what London did and plowing ahead with lots of road building? Who knows, but my hunch is that government ministers aren't actually interested in reducing congestion. After all, going by their actions the Conservatives' long-term strategy on this issue seems to be to let congestion and rise and then attack Labour for trying to address it with road-pricing. I've no doubt this is a succesful strategy in political terms, but it's terrible for the country as a whole.

The first thing to say about these is that if they are anything like as accurate as previous DfT forecasts, the actual trend in traffic will be much lower.

The other interesting thing is the section where DfT's forecasters try to explain why they got the London traffic trend so completely wrong (they forecast a drop of 1.5% between 2003 and 2010 but the actual drop was 7.8%, despite the population growing faster than anyone thought). They say:

In other words, London's experience shows that investment in public transport, congestion charging and road diets will reduce traffic sharply, which in most cases would remove the need for any new road building.We believe that the reason for this short-term model error and long-run discrepancy with other forecasts is due to:Car Ownership – the number of cars per person in London has been relatively flat over the last decade. While we have different car ownership saturation levels for different area types, including London, these may need to be re-estimated.Public Transport - London has seen high levels of investment in public transport, capacity and quality improvement on buses and rail based public transport. London will continue to see high levels of investment in public transport with increase in capacity into the future, e.g. Cross Rail. We will need to revisit our modelling on the impact this may have on car travel.Road capacity, car parking space cost and availability – There is evidence to suggest that In recent years London road capacity has been significantly reduced due to bus lanes, congestion charge and other road works. There is also a significant constraint and cost to parking in London which would reduce the demand to travel by car. We will need to revisit our modelling on the impact this may have on car travel.

So why are the government doing the opposite of what London did and plowing ahead with lots of road building? Who knows, but my hunch is that government ministers aren't actually interested in reducing congestion. After all, going by their actions the Conservatives' long-term strategy on this issue seems to be to let congestion and rise and then attack Labour for trying to address it with road-pricing. I've no doubt this is a succesful strategy in political terms, but it's terrible for the country as a whole.

Labels:

transport

Tuesday, 21 May 2013

Road crashes and smoothing the flow

As this slide from a 2012 TfL survey shows, drivers on London's main roads are much more likely to report delays due to roadworks than due to road accidents ('collisions', more accurately) - but TfL's own data shows that in reality collisions are a much more significant source of delay.

So just as Andrew Gilligan has been selling his cycling strategy as a way to reduce congestion, shouldn't we also be seeing a big push to drastically reduce the number of road crashes as a way to 'smooth the flow'?

And while delays due to roadworks have fallen, presumably due to a flurry of TfL measures designed to reduce the number and length of works on main roads, delays due to collisions remain stubbornly high and are now more than twice as large as for roadworks.

So just as Andrew Gilligan has been selling his cycling strategy as a way to reduce congestion, shouldn't we also be seeing a big push to drastically reduce the number of road crashes as a way to 'smooth the flow'?

Wednesday, 6 March 2013

The problem with 'transport poverty'

The RAC Foundation have been getting some good press coverage with their argument that we should be very concerned about the 'transport poverty' experienced by low-income households who own cars. Their preferred solution is a big cut in fuel duty, as merely "tinkering" with the rate would be akin to "rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic" according to their chair Stephen Glaister.

The RACF's argument is based on these statistics from the ONS, showing that there are around 800,000 households in the UK who are in the poorest 10% of households according to disposable income and who own a car, and that these households spend an average of £45 a week on transport, including an average of £16 a week on motor fuel. As these households all have a weekly income of less than £168 (see the top row of the table) that means that many of them are spending more than a quarter of their income on transport. The RACF calls this 'transport poverty' and thinks the way to deal with it is to make fuel cheaper.

There are several problems with this argument. First, what the RACF don't tell you is that only 31% of households in the poorest tenth of the income distribution actually own a car, compared to 96% in the richest tenth (see p.9 here). So if 'transport poverty' due to fuel costs is a problem, it is a problem only for a minority of the poor.

Second, it is likely that many of those the RACF say are in transport poverty aren't really that poor after all. Households with very low reported incomes are often there because they have suffered a temporary drop in incomes, but they could still be otherwise reasonably well off. As these academics point out,

That means the households in 'transport poverty' account for just two per cent of total motor fuel spending in the UK. By contrast, car-owning households in the top 10%, who all have disposable household incomes of over £57,000 a year, account for 21% of total motor fuel spending. So any cut in fuel tax aimed at reducing 'transport poverty' would overwhelmingly benefit the better off.

Cutting fuel duty would be an extremely bad way to reduce poverty, especially if the money has to come from elsewhere. If cuts in fuel duty were paid for reducing benefits then you would be directly transferring money from poor to rich. If the RAC Foundation are really interested in reducing 'transport poverty' then they would be better off arguing for reductions in the cost of transport modes used mostly by the poor (i.e. the bus). But the best and most tried-and-tested way to reduce poverty of any kind is to just give poor people more money.

The RACF's argument is based on these statistics from the ONS, showing that there are around 800,000 households in the UK who are in the poorest 10% of households according to disposable income and who own a car, and that these households spend an average of £45 a week on transport, including an average of £16 a week on motor fuel. As these households all have a weekly income of less than £168 (see the top row of the table) that means that many of them are spending more than a quarter of their income on transport. The RACF calls this 'transport poverty' and thinks the way to deal with it is to make fuel cheaper.

There are several problems with this argument. First, what the RACF don't tell you is that only 31% of households in the poorest tenth of the income distribution actually own a car, compared to 96% in the richest tenth (see p.9 here). So if 'transport poverty' due to fuel costs is a problem, it is a problem only for a minority of the poor.

Second, it is likely that many of those the RACF say are in transport poverty aren't really that poor after all. Households with very low reported incomes are often there because they have suffered a temporary drop in incomes, but they could still be otherwise reasonably well off. As these academics point out,

for some of those at the very bottom of the income distribution, a recorded very low income should not be taken as a sign of more general lack of resources... It might reflect the fact that some individuals experience very low income for a relatively short period of time, but that they maintain their spending at some sort of long-run level: for example, someone between jobs (who could have a 0 or very low income if measured over a sufficiently short period), or someone making a loss in their selfemployment business (which would count as a negative income).So it is very likely that many of the low-income households who own cars are only temporarily low-income. But even if we accept that these households really are poor in the usual sense and that enough of them own cars for this to be an issue (no matter how contradictory those two statements might seem), there is a third big problem with the RAC Foundation's argument. The ONS figures they cite indicate that car-owning households in the poorest 10% spend around £13m a week on fuel (830,000 households with an average weekly spend of £16), compared to spending on fuel by all households with cars of around £640m a week (19.7 million households with an average weekly spend of £32.50).

That means the households in 'transport poverty' account for just two per cent of total motor fuel spending in the UK. By contrast, car-owning households in the top 10%, who all have disposable household incomes of over £57,000 a year, account for 21% of total motor fuel spending. So any cut in fuel tax aimed at reducing 'transport poverty' would overwhelmingly benefit the better off.

Cutting fuel duty would be an extremely bad way to reduce poverty, especially if the money has to come from elsewhere. If cuts in fuel duty were paid for reducing benefits then you would be directly transferring money from poor to rich. If the RAC Foundation are really interested in reducing 'transport poverty' then they would be better off arguing for reductions in the cost of transport modes used mostly by the poor (i.e. the bus). But the best and most tried-and-tested way to reduce poverty of any kind is to just give poor people more money.

Sunday, 17 February 2013

What the congestion charge did

The London congestion charge was ten years old this week, which provoked a bit of discussion about it, most notable for the absence of anyone seriously calling for it to be abolished. As Adam Bienkov points out, its introduction in 2003 was by contrast preceded by an avalanche of criticism and predictions of doom, much of it motivated more by political grievance than by evidence or principle.

I think the best way to get a sense of the C-charge's impact is to look at Transport for London's data (here, under 'Central London Peak Count') showing how people travelled into central London during the weekday morning rush-hour between 1978 and 2011. The chart below shows the trend for people arriving by car or motorcycle only (for some reason TfL don't separate the two out).

The number of people entering central London by car (and motorbike) has clearly been trending downwards since the early 1980s, but just as clearly there was a very big drop in the early 2000s. What's really interesting is that although there was a big dros (of about 20,000) in 2003, the first year of the C-charge, that was preceded by two years of almost equally big drops in 2001 and 2002. I don't know very much about what transport policy was like back then but given that the same TfL data shows a concurrent spike upwards in bus ridership it does look rather like a generalised 'Livingstone effect' rather than something limited to the congestion charge alone, though obviously that was a very important part of it.

More recently the decline in car traffic has slowed a bit and in 2011 there was even a small increase, though hardly a noteworthy one. And if anyone is dissatisfied with current congestion levels in London, as for example the AA seem to be, the obvious answer is to campaign vigorously for an increase in the charge.

I think the best way to get a sense of the C-charge's impact is to look at Transport for London's data (here, under 'Central London Peak Count') showing how people travelled into central London during the weekday morning rush-hour between 1978 and 2011. The chart below shows the trend for people arriving by car or motorcycle only (for some reason TfL don't separate the two out).

The number of people entering central London by car (and motorbike) has clearly been trending downwards since the early 1980s, but just as clearly there was a very big drop in the early 2000s. What's really interesting is that although there was a big dros (of about 20,000) in 2003, the first year of the C-charge, that was preceded by two years of almost equally big drops in 2001 and 2002. I don't know very much about what transport policy was like back then but given that the same TfL data shows a concurrent spike upwards in bus ridership it does look rather like a generalised 'Livingstone effect' rather than something limited to the congestion charge alone, though obviously that was a very important part of it.

More recently the decline in car traffic has slowed a bit and in 2011 there was even a small increase, though hardly a noteworthy one. And if anyone is dissatisfied with current congestion levels in London, as for example the AA seem to be, the obvious answer is to campaign vigorously for an increase in the charge.

Thursday, 31 January 2013

The colour of London's commute

Today saw the release of detailed Census data on, among other things, the mode of transport those in work use to get to work. One interesting aspect of this is the rising level of cycling in London, as described here by Cyclists in the City. I'll probably be looking at that later in the week, but first here is a map which attempts to summarise the transport mix across all of London in a single image.

(Click to embiggen, and higher-quality PDF here)

What the map shows is the mix of transport to work of residents living in each part of London*, using ONS data at Middle Super Output Area (MSOA) level. Each MSOA is given an RGB colour determined by the modal share, with red colours representing travel by car, taxi or motorbike, blue travel by public transport and green cycling or walking.

The result is a fairly simple pattern, with motor vehicles predominating on London's fringes, public transport in the inner suburbs and cycling and walking in the very centre. Those tendrils of blue reaching out presumably represent major public transport links.

A few details about the mapping technique for anyone who's interested: I was inspired to use the RGB approach by James Cheshire's map of election results and after some trial and error found a fairly simple way to do it in R which I can provide more details of to anyone who asks. The data and boundaries are both from ONS, the former downloaded from Neighbourhood Statistics. The maps exclude those people of working age who are not in work, who work from home or who use some form of transport so strange that ONS only describe it as 'other'.

* Edited this to make it clear that the map is based on place of residence, following @santacreu34's helpful comment.

(Click to embiggen, and higher-quality PDF here)

What the map shows is the mix of transport to work of residents living in each part of London*, using ONS data at Middle Super Output Area (MSOA) level. Each MSOA is given an RGB colour determined by the modal share, with red colours representing travel by car, taxi or motorbike, blue travel by public transport and green cycling or walking.

The result is a fairly simple pattern, with motor vehicles predominating on London's fringes, public transport in the inner suburbs and cycling and walking in the very centre. Those tendrils of blue reaching out presumably represent major public transport links.

A few details about the mapping technique for anyone who's interested: I was inspired to use the RGB approach by James Cheshire's map of election results and after some trial and error found a fairly simple way to do it in R which I can provide more details of to anyone who asks. The data and boundaries are both from ONS, the former downloaded from Neighbourhood Statistics. The maps exclude those people of working age who are not in work, who work from home or who use some form of transport so strange that ONS only describe it as 'other'.

* Edited this to make it clear that the map is based on place of residence, following @santacreu34's helpful comment.

Sunday, 27 January 2013

Seasonality of road casualties

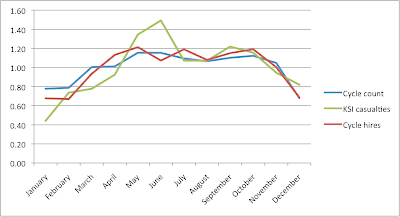

The other day a few people were discussing on Twitter whether cycling was statistically more dangerous, in terms of casualties per mile, during winter than during summer. This is something I tend to wonder while cycling home in the dark, so I thought I'd try and investigate.

I used DfT's data on reported road casualties in 2011, the most recent year available. Using just one year's data means the patterns observed may be affected by unusual weather patterns in that year, so you should treat the results as fairly provisional. Another issue with the data is unreporting, so I have focused on fatal or serious injuries which we assume are less likely to be unreported.

Most of the data cleaning and analysis was done with R, and I've copied my code at the bottom of the post. I'm no expert at R so I'm sure the code could be improved, but if anybody wants to use it then feel free.

The DfT data includes all kinds of roads casualties including those suffered while atop horses or tractors, but to keep things simple I've restricted the analysis to pedestrians, cyclists and car occupants (excluding taxis and private hire vehicles). The chart below shows the total number of fatal and serious casualties in England and Wales by road user type and month in 2011:

You can see the different patterns for each mode more clearly if you split them out:

What you see are very clear seasonal patterns for pedestrians and cyclists, with pedestrian casualties rising as winter draws in and then reaching a trough in summer, and cyclist casualties following more or less an opposite trend. There doesn't seem to be much of a pattern for car occupants, although the number of casualties is highest in December and January.

Here's the same chart for London:

The raw numbers shift around a lot because London's mode share is so different, with a lot more pedestrians and cyclists and less car traffic than in the rest of the country. But the seasonal patterns look a little different too. In particular there is a much bigger increase in pedestrian casualties towards the end of the year, and December has nearly twice as many as January.

For cyclists the obvious explanation for higher casualties in summer months is that more people cycle at that time of year. For pedestrians the logic is less clear. It doesn't seem likely that there is much more walking done in the winter months than in the summer. So the winter months, particularly December, just seem to be more risky. Nationally, the worst days for fatal or serious pedestrian casualties in 2011 were the 9th, 12th and 16th of December. There was plenty of snow that month but I wonder whether there is also some sort of 'Christmas party effect' at work here, on both pedestrians and drivers (by the way, in the US the deadliest day for pedestrians is apparently New Year's Day - see also this).

To calculate a casualty rate you divide casualties by some measure of traffic or trips. For pedestrians there's no such data that I know of. But TfL count cars and bikes passing various points on the London road network, and they have made the cycling data available via FOI in the form of this big Excel spreadsheet. This data is patchy for some count points but you can fill in the gaps with estimates based on the ones with complete data.

The other option for estimating monthly cycle trips is to use TfL's counts of cycle hires. The chart below compares monthly trends in fatal/serious bike casualties, TfL cycle counts and cycle hires, by expressing each month's figure as a ratio of the average.

Now, you probably shouldn't read too much into this comparison as it's comparing one imperfect data source with another two imperfect ones gathered at different spatial scales. But it does look like there is a bigger increase in casualties between January and June than there is in either of the trip indicators. This suggests, again very provisionally given the limitations of the data, that the number of casualties per cycling trip may be lower in the first few months of the year than in summer.

We really need a more comprehensive analysis to establish if this really is the case, but if it was what would explain it? Perhaps people who cycle all year may be more careful or skilled than those who only take to their bikes in summer. Maybe drivers may look out for cyclists more in winter. At this stage, we just don't know.

Monday, 17 December 2012

Car ownership is falling in London but car traffic is falling even faster

The last couple of weeks have seen some interesting figures confirming the decline of car culture in London. First, the 2011 Census results showed, as summarised by London City Cyclists, that the number of car-free households is growing across Inner London. Then the National Travel Survey showed that car travel per person in London fell 22% in just seven years (table NTS9904 here). Finally, as pointed out by Angus Hewlett on Twitter, here's a survey (admittedly from a fortnight ago) showing that "One in seven Britons said they were part of a household which owned a car that was only used occasionally", a figure that rose to one in five in London.

That survey suggests that car ownership has some way to fall yet in London. To get a better sense of this I plotted the trend in distance travelled by car (from DfT table TRA8905a) against the trend in the number of cars (from table VEH0204) for London and England as a whole in the chart below. Both series are rebased to start at 100 in 2000.

What this shows is that in England as whole the number of cars has risen 15% since 2000 and the distance travelled by car just 2%, while in the Greater London area the number of cars has risen 5% but the distance travelled by car has fallen 13%. The leftward turn in both lines is an indicator that distance driven per car is falling in both London and England, but it's falling particularly fast in London, in fact by 15% since 2000. The average car in London drives around 9,100 km per year (down from around 11,000 in 2000), compared to 13,800 km a year for the average car in England as a whole (also down, from 15,400 in 2000).

So it's no surprise that there are lots of 'ghost cars' hardly being driven in London, or that, particularly in the last few years, many Londoners are deciding that it's just not worth the cost and hassle of owning one. I'd expect this trend to continue for some time yet and the number of cars in London to shrink further (though it is worth bearing in mind that across London as a whole there are more cars than there were in 2000). I just hope we use the extra space freed up for useful things rather than just dropping the cost of parking even further.

That survey suggests that car ownership has some way to fall yet in London. To get a better sense of this I plotted the trend in distance travelled by car (from DfT table TRA8905a) against the trend in the number of cars (from table VEH0204) for London and England as a whole in the chart below. Both series are rebased to start at 100 in 2000.

What this shows is that in England as whole the number of cars has risen 15% since 2000 and the distance travelled by car just 2%, while in the Greater London area the number of cars has risen 5% but the distance travelled by car has fallen 13%. The leftward turn in both lines is an indicator that distance driven per car is falling in both London and England, but it's falling particularly fast in London, in fact by 15% since 2000. The average car in London drives around 9,100 km per year (down from around 11,000 in 2000), compared to 13,800 km a year for the average car in England as a whole (also down, from 15,400 in 2000).

So it's no surprise that there are lots of 'ghost cars' hardly being driven in London, or that, particularly in the last few years, many Londoners are deciding that it's just not worth the cost and hassle of owning one. I'd expect this trend to continue for some time yet and the number of cars in London to shrink further (though it is worth bearing in mind that across London as a whole there are more cars than there were in 2000). I just hope we use the extra space freed up for useful things rather than just dropping the cost of parking even further.

Thursday, 1 November 2012

The gender dimension of road danger

This BBC article about 'black box' devices in cars which monitor your driving for insurance purposes features lots of standard-issue outrage from drivers who can't see why how badly they drive should be anyone else's business but it also touches on the interesting issue of whether female drivers are safer than males. You don't have to look too hard to find plenty of commentary on this topic, but hard facts are more difficult to come by. Here's something from 2004:

What was most interesting to me is that males also account for a higher share of pedestrian casualties too: 68% of fatalities, 60% of fatal or serious injuries and 57% of slight injuries in 2011, according to this table. Other figures show that men and women do roughly equal amounts of walking, so these numbers do seem to provide some support for the idea that guys take more risks - or maybe just have worse judgement - than girls whether they're in cars or on foot.

The wider issue is that men also have more influence over transport policy and road safety, with the result that the issue is treated more as one of personal responsibility than as one of public health. The same cognitive biases that tell us we should be able to look out for ourselves ensure that we basically can't.

Male motorists were responsible for 88% of all driving offences that resulted in findings of guilt in court in England and Wales in 2002, the Home Office statistics showed. Furthermore, men committed almost all the most serious offences, such as causing death and dangerous driving: women committed just 6% of the death or bodily harm offences in 2002 and just 3% of dangerous driving offences. Men were also responsible for 96% of vehicle thefts and 97% of offences relating to motorcycles.Those are pretty huge differences, but perhaps, and I'm just speculating here, partly down to different treatment of men and women by the justice system. You can also look at the different rates at which men and women are involved in collisions resulting in injury, with the caveat that the figures don't necessarily imply anything about who's at fault. I looked at DfT's 2011 road casualties data, and found that in 85% of collision where a pedestrian died the driver of the vehicle (mostly cars but also vans, motorbikes, HGVs and a couple of bikes) was male, compared to 71% of cases resulting in serious pedestrian injury and 69% of cases resulting in slight injuries. This table suggests that men account for about 65% of the miles driven in Britain, so they do seem to have a higher rate of involvement in pedestrian casualties (trying to calculate rates for all kinds of collisions is more complicated).

What was most interesting to me is that males also account for a higher share of pedestrian casualties too: 68% of fatalities, 60% of fatal or serious injuries and 57% of slight injuries in 2011, according to this table. Other figures show that men and women do roughly equal amounts of walking, so these numbers do seem to provide some support for the idea that guys take more risks - or maybe just have worse judgement - than girls whether they're in cars or on foot.

The wider issue is that men also have more influence over transport policy and road safety, with the result that the issue is treated more as one of personal responsibility than as one of public health. The same cognitive biases that tell us we should be able to look out for ourselves ensure that we basically can't.

Wednesday, 26 September 2012

We choose how congested our roads are

This BBC article about traffic congestion in Sao Paulo carries on like 180km traffic jams are an inescapable fact of life there and congestion is an insoluble problem. They even find a professor of engineering and transport from a Sao Paulo uni to say that "No city in the world will ever manage to end congestion".

Completely ending traffic congestion may be very difficult, but there are certainly cities who have reduced it substantially by doing things which Sao Paulo has chosen not to do. Congestion charging in Stockholm, Singapore and London has sharply reduced the level of traffic in their inner cities, and there is no doubt that if they were to whack up the prices that traffic would fall even further. Many cities have also built comprehensive, high quality rail systems, and given buses priority express lanes on main roads. But in Sao Paulo, instead of a congestion charge they introduced a rotating car number-plate ban which reduced traffic in the short term but mainly encouraged people to buy more cars. The metro system is far too small given the size of the city. And historically their buses haven't been given enough priority over other traffic and so suffer from the same congestion as cars. Hence, huge traffic jams.

I'm not suggesting these are easy choices, especially for a rapidly expanding city like Sao Paulo. Most cities are not fortunate enough to have built a huge underground system over a hundred years ago when it was nice and cheap, like London did. Sao Paulo now has a growing bus rapid transit system and big plans to expand the metro, but because Brazil is a democratic country where most people have the right not to be turfed off their land, building vast infrastructure projects is much harder and slower than it is in, say, China. Likewise, it's not easy to find the money to build a subway network big enough to adequately serve a city of 20 million people, or to convince drivers that they should pay to use roads they previously used for free. Those kinds of things are very hard, which is probably why more cities don't choose to do them.

But one reason they're hard is that many people are not convinced they are worthwhile, and that in turn is partly because the public discourse around these issues seems wilfully uninformed. There are solutions available which are workable and demonstrably effective. It's one thing to consider and reject them, but to pretend they don't exist is something else altogether.

Completely ending traffic congestion may be very difficult, but there are certainly cities who have reduced it substantially by doing things which Sao Paulo has chosen not to do. Congestion charging in Stockholm, Singapore and London has sharply reduced the level of traffic in their inner cities, and there is no doubt that if they were to whack up the prices that traffic would fall even further. Many cities have also built comprehensive, high quality rail systems, and given buses priority express lanes on main roads. But in Sao Paulo, instead of a congestion charge they introduced a rotating car number-plate ban which reduced traffic in the short term but mainly encouraged people to buy more cars. The metro system is far too small given the size of the city. And historically their buses haven't been given enough priority over other traffic and so suffer from the same congestion as cars. Hence, huge traffic jams.

I'm not suggesting these are easy choices, especially for a rapidly expanding city like Sao Paulo. Most cities are not fortunate enough to have built a huge underground system over a hundred years ago when it was nice and cheap, like London did. Sao Paulo now has a growing bus rapid transit system and big plans to expand the metro, but because Brazil is a democratic country where most people have the right not to be turfed off their land, building vast infrastructure projects is much harder and slower than it is in, say, China. Likewise, it's not easy to find the money to build a subway network big enough to adequately serve a city of 20 million people, or to convince drivers that they should pay to use roads they previously used for free. Those kinds of things are very hard, which is probably why more cities don't choose to do them.

But one reason they're hard is that many people are not convinced they are worthwhile, and that in turn is partly because the public discourse around these issues seems wilfully uninformed. There are solutions available which are workable and demonstrably effective. It's one thing to consider and reject them, but to pretend they don't exist is something else altogether.

Monday, 24 September 2012

Mapping pedestrian casualties in London

The Department for Transport publish full data on recorded road casualties on data.gov.uk, and I've been playing around with the data a bit recently, partly as a way of learning some new software skills.

The map below (best viewed at full size) is one result, and shows serious and fatal pedestrian casualties in London in 2011 which were the result of collisions with bikes (in red) or cars (in turqouise). Bigger circles represent fatalities and smaller ones serious injuries.

In total there were 980 serious or fatal pedestrian casualties in London in 2011, of which 33 resulted from collisions with bikes (one fatal) and 609 resulted from collisions with cars (38 fatal). The remainder resulted from collisions with motorbikes, goods vehicles, buses and other vehicles, but I didn't show them as I wanted to keep it simple and was mainly interested in comparing cars and bikes.

Techie details: I downloaded the csv data for casualties, accidents and vehicle records for 2011, used R to merge and filter the data, used QGIS to convert the data to a shapefile, and used Tilemill to combine that shapefile with some other layers, apply stylings and export to PNG. Tilemill does some puzzling things like leaving some of the markers brigher than others for no apparent reason, but hopefully that will be ironed out in future versions.

The map below (best viewed at full size) is one result, and shows serious and fatal pedestrian casualties in London in 2011 which were the result of collisions with bikes (in red) or cars (in turqouise). Bigger circles represent fatalities and smaller ones serious injuries.

In total there were 980 serious or fatal pedestrian casualties in London in 2011, of which 33 resulted from collisions with bikes (one fatal) and 609 resulted from collisions with cars (38 fatal). The remainder resulted from collisions with motorbikes, goods vehicles, buses and other vehicles, but I didn't show them as I wanted to keep it simple and was mainly interested in comparing cars and bikes.

Techie details: I downloaded the csv data for casualties, accidents and vehicle records for 2011, used R to merge and filter the data, used QGIS to convert the data to a shapefile, and used Tilemill to combine that shapefile with some other layers, apply stylings and export to PNG. Tilemill does some puzzling things like leaving some of the markers brigher than others for no apparent reason, but hopefully that will be ironed out in future versions.

Monday, 17 September 2012

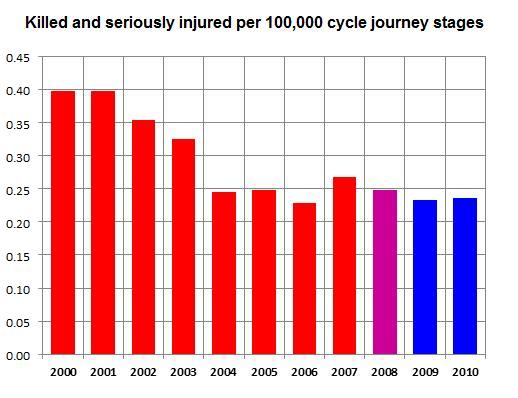

Reviewing TfL's draft road safety plan

Transport for London are currently consulting on a draft new Road Safety Plan for London which sets out proposed targets and policies for the period up to 2020. The consultation period closes on 28 September and I strongly encourage everyone to respond - there is a questionnaire you can fill out to make it a bit easier.

I plan to do a few posts analysing the draft plan in detail, as it's quite an important document. This first post looks at how TfL describe recent trends in road safety in London; the next one will probably focus on the target they propose to adopt, and the last will look at some of the policies they do and don't propose to implement.

The number of road casualties, including the number involving fatal or serious injuries (crudely abbreviated in the jargon to 'KSI' for 'killed or seriously injured'), has fallen substantially in London over the last couple of decades, and TfL are rightly keen to highlight this. The headline figure is that the number of KSI casualties in 2010 was 57% lower than the average figure for 1994-98, which has been used as the baseline until now. This means that the overall target in the original London Road Safety Plan (first published in 2001 and then updated with tougher targets in 2005), for a 50% reduction in KSI casualties by 2010, was met.

But that first Road Safety Plan didn't just set an overall target for road casualty reduction. There were targets for individual modes too, to try and ensure that casualties were reduced across the board. Following the 2005 review, these mode-specific targets were:

I'll look at some of these issues in the next post, which is about what target should be set. For now, I'd encourage everyone again to read the proposed new plan themselves and respond to the consultation.

I plan to do a few posts analysing the draft plan in detail, as it's quite an important document. This first post looks at how TfL describe recent trends in road safety in London; the next one will probably focus on the target they propose to adopt, and the last will look at some of the policies they do and don't propose to implement.

The number of road casualties, including the number involving fatal or serious injuries (crudely abbreviated in the jargon to 'KSI' for 'killed or seriously injured'), has fallen substantially in London over the last couple of decades, and TfL are rightly keen to highlight this. The headline figure is that the number of KSI casualties in 2010 was 57% lower than the average figure for 1994-98, which has been used as the baseline until now. This means that the overall target in the original London Road Safety Plan (first published in 2001 and then updated with tougher targets in 2005), for a 50% reduction in KSI casualties by 2010, was met.

But that first Road Safety Plan didn't just set an overall target for road casualty reduction. There were targets for individual modes too, to try and ensure that casualties were reduced across the board. Following the 2005 review, these mode-specific targets were:

- A 50 per cent reduction in the number of cyclists and pedestrians killed or seriously injured

- A 40 per cent reduction in the number of powered two-wheeler users killed or seriously injured

There was also a specific target to reduce the number of children killed or seriously injured by 60%.

The targets for KSI casualty reductions among cyclists and motorcyclists were not met. As the chart below (from the last annual monitoring report) shows, the number of cyclist KSI casualties fell by only 18% and the number of motorcyclist KSI casualties by 34%.

Strictly speaking, then, the original road safety strategy failed to meet its targets. TfL, however, argue that the failure to hit the targets for cyclists and motorcyclists was due to large increases in both cycling and motorcycling in London, and that the underlying casualty rate for both modes actually decreased.

I don't know much about motorcycling trends but over the longer term it is certainly true that the cycling casualty rate has fallen in London - see, for example, the chart below produced by Fullfact.org from TfL data.

There are a few things you could say in response to this argument. The most obvious is that they can't have it both ways - TfL's target was to reduce the absolute number of cycle and motorcycle casualties, and if you go back to the 2001 road safety plan you can see that this target was set in the knowledge that use of both modes was rising. Secondly, if they now think that the rate of casualties per trip or per mile travelled is more important, then why not make that the target, or better yet set a target to reduce both the rate and the number of casualties? Thirdly, it is clear from the chart above that the cycling casualty rate pretty much flatlined between 2004 and 2010. And that trend doesn't include 2011, which saw a 22% increase in fatal or serious cycling casualties, probably outpacing the growth in cycling journeys. Again, if the cycling casualty rate is so important, isn't the record of the last several years rather worrying?I don't know much about motorcycling trends but over the longer term it is certainly true that the cycling casualty rate has fallen in London - see, for example, the chart below produced by Fullfact.org from TfL data.

I'll look at some of these issues in the next post, which is about what target should be set. For now, I'd encourage everyone again to read the proposed new plan themselves and respond to the consultation.

Tuesday, 11 September 2012

More cycling than car traffic in central London during the Games?

Just a quick post speculating on a couple of interesting bits of info about transport trends in London. First, according to @bitoclass on Twitter TfL have said that cycling in London increased 22% during the Olympics (presumably compared to last year). Second, TfL have also said that vehicle traffic in central London fell considerably during the Games period, though I haven't seen any firm figures. Third, recall that even before the Games car traffic in central London was falling and bike traffic rising, with the two looking likely to converge pretty soon:

Putting these together, my guess is that cycling accounted for more journeys than cars in central London during the Games period, for the first time in probably 60 years or more. Quite a milestone if so.

[Update: Paul (@bitoclass) has kindly posted a pic of the TfL presentation slide which was the source of his factoid:

So traffic in central London was down by 5-10% in August this year compared to August 2011, and it was cycling across the Thames bridges that was up by 22%. In recent years, growth in cycling across the Thames has lagged slightly behind growth in central London (see table 8 on p.20 here) so it's quite possible that cycling in central London grew by 25% or more.

In any case, we'll probably have to wait until January or so for TfL to update the trend in my chart above. From a policy perspective, perhaps the more interesting question is whether these short-term changes in travel patterns will persist. Cycling through central London yesterday it certainly felt like the vehicle traffic was still very light, but in the absence of any more restrictions I would expect it to creep back to something close to pre-Games levels over time. Or perhaps it won't, if cycling levels stay high - after all, it does seem like once people make the leap to start cycling that a lot of them find it works for them, and in one way or another the Games have probably encouraged plenty of people to make that leap.]

Putting these together, my guess is that cycling accounted for more journeys than cars in central London during the Games period, for the first time in probably 60 years or more. Quite a milestone if so.

[Update: Paul (@bitoclass) has kindly posted a pic of the TfL presentation slide which was the source of his factoid:

So traffic in central London was down by 5-10% in August this year compared to August 2011, and it was cycling across the Thames bridges that was up by 22%. In recent years, growth in cycling across the Thames has lagged slightly behind growth in central London (see table 8 on p.20 here) so it's quite possible that cycling in central London grew by 25% or more.

In any case, we'll probably have to wait until January or so for TfL to update the trend in my chart above. From a policy perspective, perhaps the more interesting question is whether these short-term changes in travel patterns will persist. Cycling through central London yesterday it certainly felt like the vehicle traffic was still very light, but in the absence of any more restrictions I would expect it to creep back to something close to pre-Games levels over time. Or perhaps it won't, if cycling levels stay high - after all, it does seem like once people make the leap to start cycling that a lot of them find it works for them, and in one way or another the Games have probably encouraged plenty of people to make that leap.]

Monday, 10 September 2012

The fatal/serious bike casualty rate per km in London is 30x that for cars; And why bikes need more space because they take up so little

TfL have published a study (under 'Research reports' here) entitled 'Levels of collision risk in Greater London' that I think only gets really interesting on the very last page. Table 4.10 on that last page includes what I think are the first TfL calculations of casualty rates per kilometre travelled in London for different modes of transport. By combining the number of casualties in 2010, estimates of total distance travelled by each mode and assumptions on the average occupancy of each mode, they come up with the following figures for the rate of fatal or serious casualties per 100 million 'passenger kilometres'.

In case you can't read the numbers, they are 73.9 for bikes, 84 for motorcyclists, 2.5 for cars and taxis, 1.0 for buses and 0.4 for goods vehicles. So some good news for our put-upon HGV drivers there. The other interesting thing (okay, maybe only to me) in that table are the TfL estimates for average occupancy of different modes. They say the average car has 1.2 occupants, the average bus 16.6, the average bike just 1 (what, no backies?). Bear in mind that TfL already assume (table 1 on p. 67 of this PDF) that on average a bike takes up just 20% of the road space that a car does (in technical terms it has a 'PCU' or Passenger Car Unit of 0.2), a bus takes up twice as much, and so on. Put these two sets of numbers together and you get a figure for 'Persons per PCU', which is basically a measure of how efficiently each mode of transport uses road space.

In case you can't read the numbers, they are 73.9 for bikes, 84 for motorcyclists, 2.5 for cars and taxis, 1.0 for buses and 0.4 for goods vehicles. So some good news for our put-upon HGV drivers there. The other interesting thing (okay, maybe only to me) in that table are the TfL estimates for average occupancy of different modes. They say the average car has 1.2 occupants, the average bus 16.6, the average bike just 1 (what, no backies?). Bear in mind that TfL already assume (table 1 on p. 67 of this PDF) that on average a bike takes up just 20% of the road space that a car does (in technical terms it has a 'PCU' or Passenger Car Unit of 0.2), a bus takes up twice as much, and so on. Put these two sets of numbers together and you get a figure for 'Persons per PCU', which is basically a measure of how efficiently each mode of transport uses road space.

| Persons per vehicle | PCU per vehicle | Persons per PCU | |

| Cyclist | 1 | 0.2 | 5 |

| Motorbike | 1 | 0.4 | 2.5 |

| Car/taxi | 1.2 | 1 | 1.2 |

| Bus/coach | 16.6 | 2 | 8.3 |

| Goods vehicle | 1.3 | 1.65 | 0.8 |

Going by these figures, buses use the road space most efficiently (NB none of this includes energy efficiency) and cars the least efficiently (goods vehicles are there to carry goods not people so this measure has fairly limited application to them). Referring back to the figures on casualty rates, we can conclude that buses are both very safe and very space-efficient, which is great, while bicycles are very space-efficient but (relatively speaking) much less safe, which is bad. Obviously cycling could be a lot safer if London had cycling facilities like they do in Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Berlin, Stockholm and various other European cities. The high space-efficiency of cycling is, I think, just another reason that TfL should be copying what those cities have done - that is, giving bikes more space in part because they take up so little.

Monday, 3 September 2012

Robocars will change everything, somehow or other

I've seen very little discussion in Britain about driverless cars (or, if you prefer, robocars), but plenty in the US (see this and this, for example). As this long article in the Economist says, the technology has come a long way in a relatively short time, and it seems inevitable that driverless cars will start grabbing sizeable market share at some point in the next ten or twenty years. As detailed in that article, the implications could be profound. Cars driven by machine promise to be significantly safer than the human-driven variety, mainly because they will have a better sense of their own surroundings and can be programmed to not take any stupid risks. In fact, some of the technology is already in use as 'driver assitance' add-ons for existing car models:

Unfortunately, that's also the reason why all shared space schemes would probably be removed as quickly as possible. Nobody in a driverless car would want to sit there like a lemon while pedestrians merrily parade past in front of it. After all, if you clear the road of everything except other driveless cars these things will be able to go very fast. Roads that feature cyclists weaving in and out of traffic will be awful for robocars, while Dutch-style segregated lanes will be just peachy. So if the technology takes off, expect to suddenly see a lot of enthusiasm for roads that completely segregate cars from bikes and pedestrians.

Expect big changes in how we relate to cars too. Taxis might become either obsolete, if everyone owns their own robocar, or universal if nobody does (they just won't have taxi drivers). After all, taxis are expensive largely because they have to transport the taxi driver around the whole time even when there are no passengers. Eliminate that fairly hefty weight and they could become economical for everyday use, so why own your own?

The technology is likely to be transformative, in other words, but it's not completely clear in which direction (I haven't even mentioned the implications for inter-city transport, which are likely to be just as huge but more predictable). Maybe we will see cities sort themselves into two camps, one of which imposes speed limits on robocars and lets cyclists and pedestrians boss them around, while the other segregates uses, punitively cracks down on jaywalking and tries to speed as many cars through their streets as possible. The strange thing about driverless cars is that they seem like they could deliver almost every urban transport utopia you care to imagine, and some of the dystopias too. [Update: Speaking of which, by popular demand (two people on Twitter) here's Johnny Cab!

Volvo already sells a popular driver-assistance option called City Safety for around $2,000, for example. It slams on the brakes if a distance-measuring laser or camera detects a vehicle or pedestrian in the car’s path. City Safety can prevent collisions completely at speeds of up to 30kph (18mph), and at higher speeds it softens the impact.The other reason that driverless cars will be safer is that many people will recoil at the very idea and demand draconian safety regulations to allow them on the street. For example, they could be programmed to drive below the prevailing speed limit on every street, and to have 'black box' devices recording camera, sensor and movement data (the Economist says the latter is already a requirement for robocars in Nevada). Combine that with software that stops the car whenever a pedestrian steps in front of it and you would have a total revolution in city transport. Currently pedestrians and cyclists are afraid of cars because we don't know if they will stop for us, so we cede the streets to them. But if you knew that a car was not going too fast and would stop for you, what's to prevent you stepping out to cross the road in front of it? This is the kind of technology that would make the fantasised, pedestrian-ruled version of 'shared space' actually a reality.

Unfortunately, that's also the reason why all shared space schemes would probably be removed as quickly as possible. Nobody in a driverless car would want to sit there like a lemon while pedestrians merrily parade past in front of it. After all, if you clear the road of everything except other driveless cars these things will be able to go very fast. Roads that feature cyclists weaving in and out of traffic will be awful for robocars, while Dutch-style segregated lanes will be just peachy. So if the technology takes off, expect to suddenly see a lot of enthusiasm for roads that completely segregate cars from bikes and pedestrians.

Expect big changes in how we relate to cars too. Taxis might become either obsolete, if everyone owns their own robocar, or universal if nobody does (they just won't have taxi drivers). After all, taxis are expensive largely because they have to transport the taxi driver around the whole time even when there are no passengers. Eliminate that fairly hefty weight and they could become economical for everyday use, so why own your own?

The technology is likely to be transformative, in other words, but it's not completely clear in which direction (I haven't even mentioned the implications for inter-city transport, which are likely to be just as huge but more predictable). Maybe we will see cities sort themselves into two camps, one of which imposes speed limits on robocars and lets cyclists and pedestrians boss them around, while the other segregates uses, punitively cracks down on jaywalking and tries to speed as many cars through their streets as possible. The strange thing about driverless cars is that they seem like they could deliver almost every urban transport utopia you care to imagine, and some of the dystopias too. [Update: Speaking of which, by popular demand (two people on Twitter) here's Johnny Cab!

Friday, 29 June 2012

Rising cycling casualties: policy needs to catch up, and fast

We had new statistics on road casualties in 2011 at both national and London level yesterday, and in both cases the figures on cycling make for grim reading. The number of cyclists killed or seriously injured increased from 2010 levels by 15% nationally and by an even worse 22% in London. As the chart below shows, fatal or serious cycle casualties in London are down over the long term but up sharply in recent years.

Naturally people are interested in what this means for the rate of cycling casualties per trip or mile cycled. Some other DfT figures released yesterday indicate that miles cycled nationwide rose by only 2%, which implies a large increase in the casualty rate (see road.cc's number crunching). TfL will probably not release statistics on cycle trips in 2011 until their next Travel in London report (probably just after Christmas) but I don't think anyone seriously expects cycling to have grown more than 22% in a single year.

And anyway, even if I'm wrong and cycling levels were up by more than 22%, would that make such a large increase in the absolute number of casualties okay? To illustrate the point, say the number of trips cycled in London grew by 25% each year for five years and the number of cyclists killed or seriously injured by 20%. Going by TfL's figures for 2010 from this report and assuming everything else stayed the same, then by 2015 we'd have 1.5m cycling trips a day, a modal share of 6%, a lower cycling casualty rate BUT over 1,000 cyclists killed or seriously injured a year. Should that really be considered a success?

Of course that's a slightly unrealistic scenario, but the point is that cycling casualties are rising at an alarming rate, in part because more and more people are choosing to cycle (for whatever reason). We all like to see cycling growing, but if it is not to result in truly horrific numbers of deaths and injuries then we need a complete transformation in cycling conditions in this city.

Fortunately there is, on the face of it, a political consensus around this issue, as in the run-up to the 2012 mayoral election every major candidate endorsed the London Cycling Campaign's 'Go Dutch' manifesto, which entails dropping our current approach to road design and embracing the Dutch ethos, including high-quality segregated cycle lanes on busy main roads. So really there should be no debate about the general principle of what do do, just about the details of how to do it. I hope the forthcoming London Assembly transport committee inquiry into cycle safety adopts this approach.

Of course Transport for London and various individual politicians will say that it can't be done in London because we don't have the space on our roads. But I think these latest casualty figures show that we have no choice but to make the space. To turn the old slogan on its head, we haven't built the infrastructure but the cyclists are coming anway, and as a result they're getting killed or injured in greater and greater numbers. They have forced the issue, and policy has to catch up.

Wednesday, 11 April 2012

10% of Inner London gets to work by bike

A while back I posted an analysis of Census data showing the trend in the proportion of people who cycle to work in Inner and Outer London from 1971 to 2001. We won't have equivalent figures from the 2011 Census for several months, but we can use another source of information on travel to work, the Labour Force Survey (which I mentioned yesterday when talking about trends in car travel).

The chart below shows the proportion of LFS respondents in Inner and Outer London who reported using bicycles as their main mode of transport to work between 2004 and 2011. One important thing to note is that in each year the data is from the October to December quarter of the survey only, so differences in autumn weather from year to year will affect the results somewhat. Also, as with the car data yesterday these figures are estimates based on relatively small samples of people, and so they have largish confidence intervals around them. This means that there are few if any statistically significant year-to-year changes - but for both Inner and Outer London the trend over the whole period is fairly clear.

In late 2004 around 6% of Inner London workers commuted by bike, rising to around 10% in late 2011. For reference, the share who travelled to work by car fell from 20% to 16% over the same period. A few more years of this and they'll be level pegging.

As we have seen before, cycling is much less common in Outer London, but at least it now seems to be rising, from a 2% share in 2004 to 3.5% in 2011. Not shown is the trend in the rest of the UK, but it's basically flat at around 3% throughout.

[Note: The LFS data here was downloaded from the Economic and Social Data Service]

The chart below shows the proportion of LFS respondents in Inner and Outer London who reported using bicycles as their main mode of transport to work between 2004 and 2011. One important thing to note is that in each year the data is from the October to December quarter of the survey only, so differences in autumn weather from year to year will affect the results somewhat. Also, as with the car data yesterday these figures are estimates based on relatively small samples of people, and so they have largish confidence intervals around them. This means that there are few if any statistically significant year-to-year changes - but for both Inner and Outer London the trend over the whole period is fairly clear.

In late 2004 around 6% of Inner London workers commuted by bike, rising to around 10% in late 2011. For reference, the share who travelled to work by car fell from 20% to 16% over the same period. A few more years of this and they'll be level pegging.

As we have seen before, cycling is much less common in Outer London, but at least it now seems to be rising, from a 2% share in 2004 to 3.5% in 2011. Not shown is the trend in the rest of the UK, but it's basically flat at around 3% throughout.

[Note: The LFS data here was downloaded from the Economic and Social Data Service]

Monday, 9 April 2012

People are using their cars less (but still quite a lot)

The chart below shows my calculation of daily car travel in miles per person in Britain from 1949 to 2010, derived from these DfT statistics on car travel and population data from the Census and from ONS mid-year estimates.

According to these figures, per capita daily car travel peaked in 2004 at 11.7 miles and has been trending slowly downwards since then. A couple of caveats are probably in order at this point: we are in a recession, which usually reduces travel, and while these figures are per person, strong population growth could in future increase total car travel even if the per capita average continues falling. Finally, the reduction in car traffic is slightly offset by a rise in light van traffic over the same period.

We've also got data for London, though only going back to 1993. The chart below uses population data from ONS but published on the London datastore. The trend here is quite different, already flatlining in 1993 and falling fairly consistently from the turn of the millennium. While car travel per capita has fallen across London, the drop is particularly large in Inner London, down 28% over the period. The average Inner London now travels a shade under four miles a day by car, compared to just over six for Outer Londoners and eleven for the average Briton.

Lastly, much of the talk in the US is about whether car travel is particularly falling among younger people. To try and get a feel for this I looked at data from the Labour Force Survey on the main mode of transport people use for getting to work. Obviously the caveat here is that commuting is only a subset of all travel, but it's the best we can do for now. The chart below shows the proportion of people in broad age groups who reported travelling to work by car in 2004 (the earliest year I could find) and in 2011.

It's really important to emphasise here that this is based on a sample survey, so the estimates have confidence intervals around them (the little black lines). This means that in most cases the change is not statistically significant - including the apparent increase in car use among 16-19 year olds. The only age bands in which there was a clear, statistically significant change over the period were 25-29, 30-34, 35-39 and 50-54 year olds, all of whom were less likely to drive to work in 2011 than in 2004. So there's evidence of a fall in car commuting, but mainly by the 'young-ish' rather than the young (only around half of whom commute by car anyway).

Monday, 16 January 2012

Long-run trend in commuting into central London

[Cross-posted to London Transport Data]

The first statistics on commuting into central London were collected in the 1850s (of which more later), but the first figures comparable to the present date from around a century later. The chart below shows the trend since 1956 in the number of people (in thousands) measured as entering central during the weekday morning peak, broken down by whether they used rail (national rail, London Underground or TfL), bus or private transport (car, coach, taxi, cycle and motorcycle). NB, walking isn't included.

The number of morning commuters peaked at about 1.25 million in 1962 and then fell through most of the next twenty years. The pattern over the last thirty years is dominated by peaks and troughs linked to London's economic performance, with notable booms and busts in the late 1980s, early 2000s and in 2007-08. Rail is the dominant mode throughout this period, even more so in recent years, reaching 79% of the total in 2010. In fact the more interesting changes happened on the road and only really show up when you leave rail out. Detailed data on road traffic only starts in 1969 but the chart below interpolates back to estimates from 1961 to show the broad modal split of road commuting over a nearly 50-year span. It shows buses and cars twice swapping places as the dominant mode of transport for commuters, with bus ridership sliding throughout the 60s and 70s before shooting up again in the early 2000s. Interestingly, this latter shift seems to have started before the introduction of the congestion charge: the number of car commuters into central London fell by nearly a quarter between 2000 and 2002, before the C-charge was introduced in 2003.

The most notable trends in the last decade have been the continuing fall in the car share of commuting, and the rise in cycling. The chart below shows cycling's share of road commuting into central London since 1969. In the early 1970s cycling accounted for just 1% of road commuting (and therefore a much smaller share of total commuting), but by 2010 this had risen to 12%. Given the combined motorcycle/cycle figure in 1961 was 13%, it seems fairly plausible that cycling now accounts for a higher share of central London commuters than at any point in the past. Also, if current trends continue (a big if) it won't be long before more people are coming into central London on two-wheelers than in cars.

I mentioned at the start that these kind of statistics were first collected in the 1850s. This refers to a survey by Charles Pearson, who hired 'traffic-takers' to stand 'at all the principal entrances to the city of London, to take their station from eight o’clock in the morning till eight o’clock at night' and count the number of persons and vehicles leaving or entering the City over the twelve-hour period. The City was a much larger part of 'London' in the 1850s than it is now, and Pearson measured somewhat different flows and used a different methodology, but his results, shown in the table below, are still fascinating.

Estimated number of persons and vehicles going into and out of the City daily in 1854, counting them all both ways.

Railways were still in their infancy and there was no Tube yet, but the most striking result here is how many people walked into Central London. That's not so surprising, as London was much smaller and denser than it is today so most people would have been within an hour's walk of the City. It's frustrating that we don't have comparable figures on walking today (at least, not that we could easily find) but as the city is so much more spread out you would expect walking's share to be much lower, though still significant.

The first statistics on commuting into central London were collected in the 1850s (of which more later), but the first figures comparable to the present date from around a century later. The chart below shows the trend since 1956 in the number of people (in thousands) measured as entering central during the weekday morning peak, broken down by whether they used rail (national rail, London Underground or TfL), bus or private transport (car, coach, taxi, cycle and motorcycle). NB, walking isn't included.

The number of morning commuters peaked at about 1.25 million in 1962 and then fell through most of the next twenty years. The pattern over the last thirty years is dominated by peaks and troughs linked to London's economic performance, with notable booms and busts in the late 1980s, early 2000s and in 2007-08. Rail is the dominant mode throughout this period, even more so in recent years, reaching 79% of the total in 2010. In fact the more interesting changes happened on the road and only really show up when you leave rail out. Detailed data on road traffic only starts in 1969 but the chart below interpolates back to estimates from 1961 to show the broad modal split of road commuting over a nearly 50-year span. It shows buses and cars twice swapping places as the dominant mode of transport for commuters, with bus ridership sliding throughout the 60s and 70s before shooting up again in the early 2000s. Interestingly, this latter shift seems to have started before the introduction of the congestion charge: the number of car commuters into central London fell by nearly a quarter between 2000 and 2002, before the C-charge was introduced in 2003.

The most notable trends in the last decade have been the continuing fall in the car share of commuting, and the rise in cycling. The chart below shows cycling's share of road commuting into central London since 1969. In the early 1970s cycling accounted for just 1% of road commuting (and therefore a much smaller share of total commuting), but by 2010 this had risen to 12%. Given the combined motorcycle/cycle figure in 1961 was 13%, it seems fairly plausible that cycling now accounts for a higher share of central London commuters than at any point in the past. Also, if current trends continue (a big if) it won't be long before more people are coming into central London on two-wheelers than in cars.

I mentioned at the start that these kind of statistics were first collected in the 1850s. This refers to a survey by Charles Pearson, who hired 'traffic-takers' to stand 'at all the principal entrances to the city of London, to take their station from eight o’clock in the morning till eight o’clock at night' and count the number of persons and vehicles leaving or entering the City over the twelve-hour period. The City was a much larger part of 'London' in the 1850s than it is now, and Pearson measured somewhat different flows and used a different methodology, but his results, shown in the table below, are still fascinating.

Estimated number of persons and vehicles going into and out of the City daily in 1854, counting them all both ways.

| Omnibus | 88,000 |

| Other vehicles | 52,000 |

| River steamers | 30,000 |

| Via Fenchurch St and London Bridge rail | 54,000 |

| Foot passengers | 400,000 |

Railways were still in their infancy and there was no Tube yet, but the most striking result here is how many people walked into Central London. That's not so surprising, as London was much smaller and denser than it is today so most people would have been within an hour's walk of the City. It's frustrating that we don't have comparable figures on walking today (at least, not that we could easily find) but as the city is so much more spread out you would expect walking's share to be much lower, though still significant.

Sunday, 18 September 2011

Congestion and road pricing links

It's been an interesting couple of days in the wacky world of congestion and road pricing. First, the House of Commons Transport Committee tried to identify some ways to address congestion without resorting to road pricing and came up with ... not very much really, just a lot of well-meaning but essentially small-bore stuff about trying to make motorists behave better or think smarter, and the usual griping about roadworks. None of these are going to have a very big impact on congestion, as the committee probably knows. So this report is actually another piece of evidence in support of road pricing, if only by omission.

Secondly, a much less noticed but more rigorous analysis of the issue was provided by the IFS in its Mirrlees Review of Taxation, which looked at a range of issues including 'Taxes on Motoring'. They make the very important point that while the existing fuel tax regime acts as a sort of indirect tax on road use, increasing fuel efficiency has made it less and less effective in this role, which means that our only national brake on congestion gets weaker over time:

Lastly, Dave Hill of the Guardian makes the case for the crucial role of road pricing in particular and transport policy in general in fostering urban prosperity and quality of life here.

Secondly, a much less noticed but more rigorous analysis of the issue was provided by the IFS in its Mirrlees Review of Taxation, which looked at a range of issues including 'Taxes on Motoring'. They make the very important point that while the existing fuel tax regime acts as a sort of indirect tax on road use, increasing fuel efficiency has made it less and less effective in this role, which means that our only national brake on congestion gets weaker over time:

However it is done, we do not underestimate the political difficulties of introducing road pricing nationally. But in addition to the long-standing case for such a move, we need urgently to wake up to the fact that, if the UK and other countries are to meet their targets for reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, petrol and diesel use by motor vehicles is likely to have to fall and eventually end as alternative technologies are introduced. This will leave the UK with no tax at all on the very high congestion externalities created by motorists. So, if we all end up driving electric cars, it seems that we shall have no choice but to charge for road use. It will be much easier to introduce such charges while there is a quid pro quo to offer in terms of reduced fuel taxes ... Of all the challenges raised in this volume, this seems to us one that is simply inescapable. It may be another ten years before change becomes urgent, but urgent it will become and the sooner serious advances are made to move the basis of charging to one based on congestion the better.

(emphasis added)

Lastly, Dave Hill of the Guardian makes the case for the crucial role of road pricing in particular and transport policy in general in fostering urban prosperity and quality of life here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)