Here are some contributory factors that come to mind:

- routinised lifestyles and a high proportion of mothers as housewives

- lower car ownership, with playable streets

- more local employment and local schools, to which people walked or cycled

- availability of local trade, ditto

- ties that overlapped in the spheres of leisure and workplace as well as home environment

- a heritage of deference to authority (which depended often on unhealthy, disempowering relationships)

- housing that people valued.

Sounds about right to me, and it highlights how an era that many seem to hearken back to resulted from a unique conjuncture of historical trajectories, some of which we probably wouldn't want to turn back even if we could, the lack of autonomy for women being an example.

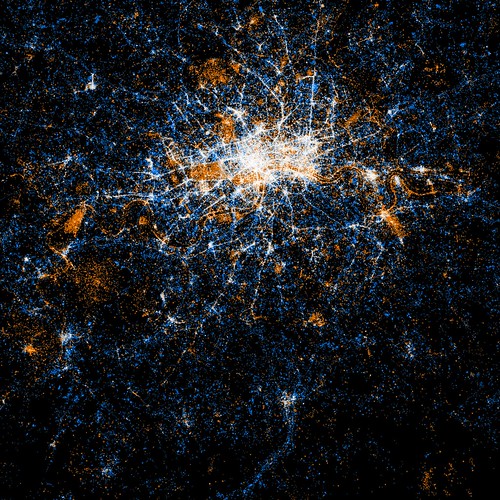

I think it's particularly important to emphasise the geographically circumscribed nature of society and the economy at the time: overseas trade was much less significant in the 1950s and 1960s than today (see chart below, from here), which meant that effectively more people were producing for their neighbours, near-neighbours or compatriots, while both transport and communication technologies were more expensive and less widely available. That all meant that people devoted more time and attention to those nearby and so local ties were stronger, but partly because there was just less choice then. We've got much more choice now in what we consume and where we go and who we talk to - the potential spatial scope of our social networks has grown massively, so it's no wonder that local ties have weakened.

That's obviously not to say that the change has been unambiguously good. Maybe we've unwittingly crossed a threshold whereby the strength of local networks has collapsed more than we would consciously want. And anyone who wants to foster the desirable aspects of strong local networks probably needs to work a lot harder at fostering them (Kevin has some ideas), because I don't think the economic and social conditions that produced them in the post-war years are going to come back any time soon.