Injuries and deaths as a result of road collisions impose huge costs on our society, both on the people directly involved and an others more indirectly affected. While everyone will react differently to being in a road collision, we can try to quantify the average social and economic impacts in order to get at the overall cost to society as a whole and hopefully provide a further incentive for change.

The Department for Transport estimates the total cost of a road fatality to be around £1.7 million, of a serious casualty around £190,000, and of a slight casualty around £15,000. These are arrived at using the 'willingness to pay' economic method, and are meant to take into account the 'human costs' of suffering and grief, lost economic output due to injury or death and the costs of medical treatment.

Using these figures DfT estimates the total cost of reported road casualties in Britain in 2001 to be around £15.6 billion, and the total cost including unreported casualties to be up to around £34.8 billion.

Using the same average costs, Transport for London estimates the total cost of reported road casualties in London in 2011 to be around £2.35 billion. Since TfL also provide data on the location, mode and severity of each casualty in London in 2012, we can use the same figures to see how these costs vary from borough to borough and mode to mode.

The chart below shows the estimated total social and economic cost of reported road casualties in 2012 by borough and the casualty's mode of transport, using DfT's averages. There's a table with the same figures below the fold.

There are huge variations between boroughs in terms of both the scale and the composition of the costs associated with road casualties. The total cost in lowest in Kingston at around £27 million, and highest in Westminster at around £128 million. In Outer London boroughs car occupants account for a higher proportion of casualties and therefore of costs, while in some Inner London boroughs pedestrians and cyclists account for over half the costs, reaching 58% of the total in Westminster and 69% in the City of London. Across all boroughs the total costs by mode come to £523m for pedestrians, £345m for cyclists, £674m for car occupants and £518m for other modes (motorcycles, buses, taxis, goods vehicles, etc).

It's worth emphasising that these figures are bound to be an underestimate. Not only do they cover only reported casualties and excluse those that go unreported, but they arguably don't capture the full range of costs. Road danger results in 'avertive' behaviour, where people go out of their way to avoid particular danger-spots or choose to take modes of transport which are safer but slower or more expensive. These costs are very difficult to quantify and so they aren't included in the DfT figures.

Also, the average costs per casualty are likely to be higher in London than in other parts of the country, given the higher wages in London and therefore higher costs of lost output and higher 'willingness to pay' to avoid casualties.

It may sound callous to talk about road casualties in terms of money but this is really just a way to try and quantify the non-monetary costs in a rigorous way. And I think these figures could be a useful tool for campaigners too. Some boroughs don't seem to attach enough importance to road safety (or road danger reduction, if you prefer), but if the government were to levy fines on them in proportion to these costs I think it would concentrate minds pretty rapidly.

Monday, 29 July 2013

Wednesday, 17 July 2013

London shows you don't need new roads to tackle congestion

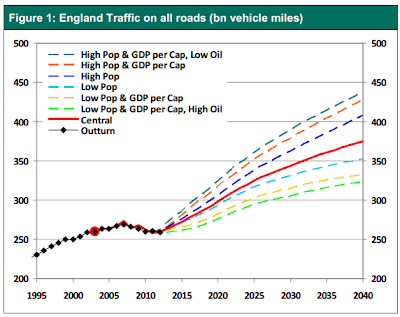

The Department for Transport has released traffic forecasts which, like Department for Transport forecasts always do, predict huge increases in traffic over the coming decades.

The first thing to say about these is that if they are anything like as accurate as previous DfT forecasts, the actual trend in traffic will be much lower.

The other interesting thing is the section where DfT's forecasters try to explain why they got the London traffic trend so completely wrong (they forecast a drop of 1.5% between 2003 and 2010 but the actual drop was 7.8%, despite the population growing faster than anyone thought). They say:

So why are the government doing the opposite of what London did and plowing ahead with lots of road building? Who knows, but my hunch is that government ministers aren't actually interested in reducing congestion. After all, going by their actions the Conservatives' long-term strategy on this issue seems to be to let congestion and rise and then attack Labour for trying to address it with road-pricing. I've no doubt this is a succesful strategy in political terms, but it's terrible for the country as a whole.

The first thing to say about these is that if they are anything like as accurate as previous DfT forecasts, the actual trend in traffic will be much lower.

The other interesting thing is the section where DfT's forecasters try to explain why they got the London traffic trend so completely wrong (they forecast a drop of 1.5% between 2003 and 2010 but the actual drop was 7.8%, despite the population growing faster than anyone thought). They say:

In other words, London's experience shows that investment in public transport, congestion charging and road diets will reduce traffic sharply, which in most cases would remove the need for any new road building.We believe that the reason for this short-term model error and long-run discrepancy with other forecasts is due to:Car Ownership – the number of cars per person in London has been relatively flat over the last decade. While we have different car ownership saturation levels for different area types, including London, these may need to be re-estimated.Public Transport - London has seen high levels of investment in public transport, capacity and quality improvement on buses and rail based public transport. London will continue to see high levels of investment in public transport with increase in capacity into the future, e.g. Cross Rail. We will need to revisit our modelling on the impact this may have on car travel.Road capacity, car parking space cost and availability – There is evidence to suggest that In recent years London road capacity has been significantly reduced due to bus lanes, congestion charge and other road works. There is also a significant constraint and cost to parking in London which would reduce the demand to travel by car. We will need to revisit our modelling on the impact this may have on car travel.

So why are the government doing the opposite of what London did and plowing ahead with lots of road building? Who knows, but my hunch is that government ministers aren't actually interested in reducing congestion. After all, going by their actions the Conservatives' long-term strategy on this issue seems to be to let congestion and rise and then attack Labour for trying to address it with road-pricing. I've no doubt this is a succesful strategy in political terms, but it's terrible for the country as a whole.

Labels:

transport

Monday, 1 July 2013

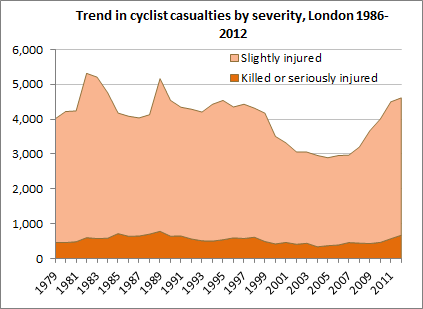

Trends in London cycling casualties

Last Friday Transport for London released statistics on London's recorded road casualties in 2012, along with (for the first time) some useful raw data - see under 'Data extracts' here. I've used the new figures to update some long-term trends in cycling casualties in London. Unfortunately they don't make for cheerful reading.

The first chart shows the trend in total recorded cycling casualties, split into slightly injured and killed or seriously injured ('KSI', in the rather inadequate jargon). As you can see, total casualties peaked in the early and late 1980s, fell fairly steadily in the early years of this century but rose again from about 2007, reaching just over 4,600 in 2012.

The large number of slight casualties hides the trend in fatl or serious casualties so the next chart isolates those. It show a slightly different trend, peaking in 1989 at almost 800 a year and with a sharp increase in the last few years to 671 in 2012.

These trends are pretty grim for cyclists, which as the chart below shows have comprised a seemingly ever-increasing share of London's fatal or serious road casualties over the last decade, reaching a fairly shocking 22% in 2012. Maybe instead of asking that cyclists get a share of investment equal to their mode share (around 2%) we should be demanding they get the same as their share of casualties?

Finally, let's have a look at cycling in the City of London, the tiny square mile at the heart of London which so many of us have to cycle through even if the people who run the place would rather we didn't. The first chart here shows a rising trend in total cycling casualties in the City since 1986.

And the second chart shows the trend in fatal or serious cycling casualties.

It should be fairly clear that the City has a big problem with cycling safety. Bear in mind that its Local Implementation Plan sets a target to reduce the number of fatal or serious casualties (of any type) to a yearly average of 39 by 2013 (4.54 here). But instead the trend is going in the opposite direction, with 49 killed or seriously injured in 2011 and 58 in 2012. As the chart above shows, cycling accounts for much of this increase, so maybe the City needs to radically change its approach to cycling provision if it's to have any chance of meeting its own targets.

One of the questions people reasonably ask when they see these kind of trends is whether casualties are rising faster than the number of people cycling, which we know has grown a lot in recent years. TfL point out that cycling on London's main road network has increased by 60% since 2005/06, but that overstates the growth in cycling trips around London as a whole, which as of 2011 had increased by only around 16% over the 2005-09 average compared to a 36% increase in fatal or serious casualties (compare table 3.5 here and table 2 here). So it's safe to say that the cycling casualty rate has worsened over the last few years, even if it's better than it was in the 1980s.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)