If you want to produce a map of population density the usual way to go about it is to get some Census data on density in different zones (wards, Census tracts, etc) and plot it like the map below, which shows 2011 population density in London at Middle Super Output Area (MSOA) level (darker colours represent higher density).

This approach has the virtues of being quick and a fairly standard approach, but there are serious drawbacks too. The most serious one is that this map doesn't really show you the distribution of population, because it hides the fact that across large swathes of London there are no people whatsoever. Much of London's area comprises water (only partially represented in the map above in the shape of the Thames), parkland, transport, industrial or commercial property, or some other non-residential use.

Not only do

choropleth maps of this kind not show these variations in land use, but by analogy the calculation of population density across the whole area of each zone will greatly understate the 'real' density of population in zones with little residential land. Look at the very centre of the map, for example. That white blob is the City of London, and this map is telling us that it has very low population density, similar to London's semi-rural outskirts. In the sense of 'population per hectare of all land', that's true, because most of the City comprises commercial property with nobody living there. But there are some residential areas in the City and in these areas people live at

fairly high densities. So in terms of 'population per hectare of residential land' the map is quite misleading.

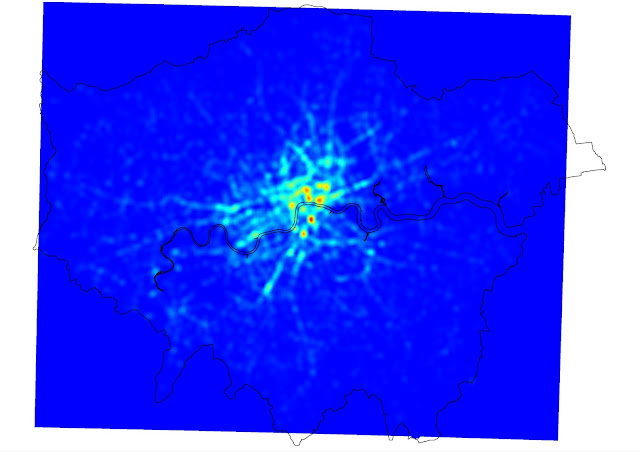

We may get a more realistic picture from a

dasymetric map. This type of map combines the same kind of population data with separate data on land use, so that only the relevant areas are highlighted. For our purposes we are interested in residential land, and for that I went to the European Environment Agency's

Urban Atlas maps of urban land use based on 2006 satellite data. Using

R I extracted from the London map the area covered by continuous or discontinuous 'urban fabric' and also any construction sites, as most of these will be for housing. While 'urban fabric' sounds a bit general there are categories for industrial, commercial, transport, water, green, forest, leisure and other land uses so I was fairly confident that it represented

residential land reasonably accurately.

Using

QGIS I joined this residential land layer to the same data on population at MSOA level from the Census, recalculated population density in each MSOA on the basis of the residential land only, linked the results back onto the residential layer, and mapped it:

Click on the image for a bigger version (or find the full size 7mb behemoth

here).

What we end up with is, I think, a much better map of London's population density, because it shows only the residential areas (or a close approximation) and it doesn't artificially reduce density in mostly non-residential areas like the City or indeed Bromley or neighbourhoods bordering the Lea valley.

Using this approach also changes the ranking of boroughs in terms of population density. Measured in gross terms (that is, across all land), Islington had the highest population density of any London borough in 2011 at 139 people per hectare. But looking only at residential land Islington's

net population density was 181 people per hectare - higher, but not nearly as high as Tower Hamlets at 256. And this makes sense - Tower Hamlets has large areas of non-residential land (much of Canary Wharf, for example), but what residential land it does have tends to be pretty densely occupied.

I should say that this map is far from a perfect representation of reality. It has a number of flaws, such as the combination of land use data from 2006 with population data from 2011, so that it undoubtedly misses out some residential areas created in the interim. It divides the entire range of population densities into only four categories which are then treated as internally identical. And similarly, like all spatially aggregated data it hides variation within each zone, in this case MSOAs. I could have used the smaller Output Area geography, but it would have taken more time and more computing power than I wanted.

Update, 1 Feb: Here's a scrollable, zoomable version of the full-size map for you to explore: