Wednesday, 27 July 2011

London Transport Data blog

Together with some associates, I have started up a new blog which will cover London transport data. We gave it the witty name London Transport Data, and you can find it here, with a mission statement of sorts here. Expect some cross-posting, starting today.

Labels:

admin

Trends in motor vehicle traffic in London

The Department for Transport published new estimates of motor vehicle traffic yesterday, covering the years up to 2010 and quarters up to Q1 2011. There are a range of accompanying data tables but we have picked out a few trends specific to London. All the charts below show indexed trends, with 1993 set to 100.

Traffic in London and England

Overall motor vehicle has fallen for three years in a row in both London and England as a whole, but in London this was preceded by a nine-year stretch of basically flat traffic levels, while traffic continued to grow quite strongly in England as a whole.

Traffic in Inner and Outer London

Within London there has been a clear divergence in the traffic trend between Inner and Outer London. Between 1999 and 2007 traffic grew slightly in Outer London and fell slightly in Inner London, while since 2007 traffic has fallen in both areas, but faster in the inner city.

Car vs non-car motor vehicle traffic in London

Car traffic in London as a whole has been falling since 2002, while non-car motorised traffic continued growing strongly until 2007, from which point it has dropped sharply in the last three years.

You can download the data for the charts in CSV format here.

Originally posted at London Transport Data.

Traffic in London and England

Overall motor vehicle has fallen for three years in a row in both London and England as a whole, but in London this was preceded by a nine-year stretch of basically flat traffic levels, while traffic continued to grow quite strongly in England as a whole.

Traffic in Inner and Outer London

Within London there has been a clear divergence in the traffic trend between Inner and Outer London. Between 1999 and 2007 traffic grew slightly in Outer London and fell slightly in Inner London, while since 2007 traffic has fallen in both areas, but faster in the inner city.

Car vs non-car motor vehicle traffic in London

Car traffic in London as a whole has been falling since 2002, while non-car motorised traffic continued growing strongly until 2007, from which point it has dropped sharply in the last three years.

You can download the data for the charts in CSV format here.

Originally posted at London Transport Data.

Monday, 18 July 2011

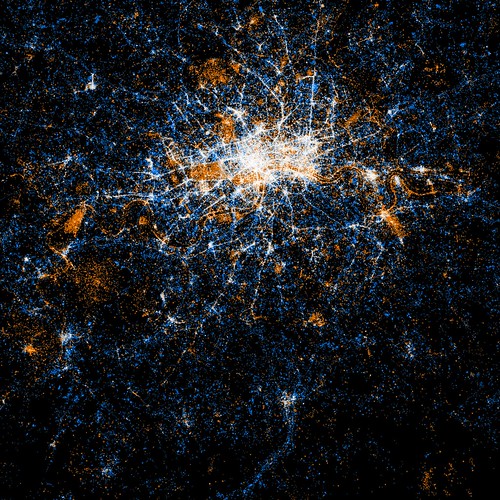

See something or say something - Eric Fischer's flickr/Twitter maps

I was going to write up some thoughts on what we can learn about cities from Eric Fischer's beautiful new maps of tweets and flickr photos (London above), but this interview with Eric pretty much covers it. I would just add that 'flickr density' might be a useful proxy for amenity value in economic or geographic analysis.

You should also go enjoy the full set of maps here. The man's a genius.

Labels:

maps

Tuesday, 5 July 2011

Where the NIMBYs are

NatCen have a new report out summarising the results of a survey (commissioned by the previous government) into attitudes towards housing in England. There's lots of interesting stuff in there about tenure aspirations and so on, but I wanted to focus on the section about attitudes towards new housing supply.

Survey respondents were asked whether they would support or oppose more homes being built in their local area. The headline result is that only 29% of respondents support more homes being built in their local area, while 46% were opposed and 23% were neither supportive or opposed. But I'm more interested in the underlying factors, so the charts below break down the results by a variety of categories, with those who neither supported nor opposed new housing excluded for the sake of clarity.

It's pretty striking that opposition to new housing supply is highest in Outer London and lowest in Inner London. Inner London is the only part of the country to have a substantial plurality in favour of new supply.

In general, it is in larger urban areas where support for new housing is highest and in suburbs, small towns or the country where opposition is strongest. But are attitudes just a function of geography or does that mask some other more important factors?

We can't really isolate causation from this data but the breakdown by household income is rather suggestive. It shows that the poorest households are the most supportive of new housing supply and those in the upper half of the income distribution the most opposed.

Finally, there are stark differences according to the current housing tenure of the respondent. People in social housing are on average in favour of new housing supply, people who rent privately are basically split, and a large plurality of owner occupiers are opposed.

The fact that Inner London has a higher proportion of low income and/or renting households probably goes a long way to explaining why it has the highest support for new supply in the country. The tenure comparison also supports the case for an economic rationale behind attitudes to new supply. Owner occupiers would tend to have the least need for new supply and the most to lose if new supply brings down house prices, while social housing tenants have little incentive to worry about lower local prices and are more likely to know someone who needs a home or be in need of one themselves. And perhaps private renters are somewhere in the middle.

As a final point, I'd just like to emphasise that we tend to think of attitudes to new housing supply as a personal matter, but it has potentially huge implications for the lives of other people. If we succesfully oppose new housing supply in our local area we make it more difficult for people to find a decent, affordable place to live. We may not ever meet those people or even be aware of their existence, but they exist alright. This is in large part a moral issue, and I think we should be willing to discuss our attitudes to it in terms of their moral consequences.

Survey respondents were asked whether they would support or oppose more homes being built in their local area. The headline result is that only 29% of respondents support more homes being built in their local area, while 46% were opposed and 23% were neither supportive or opposed. But I'm more interested in the underlying factors, so the charts below break down the results by a variety of categories, with those who neither supported nor opposed new housing excluded for the sake of clarity.

It's pretty striking that opposition to new housing supply is highest in Outer London and lowest in Inner London. Inner London is the only part of the country to have a substantial plurality in favour of new supply.

In general, it is in larger urban areas where support for new housing is highest and in suburbs, small towns or the country where opposition is strongest. But are attitudes just a function of geography or does that mask some other more important factors?

We can't really isolate causation from this data but the breakdown by household income is rather suggestive. It shows that the poorest households are the most supportive of new housing supply and those in the upper half of the income distribution the most opposed.

Finally, there are stark differences according to the current housing tenure of the respondent. People in social housing are on average in favour of new housing supply, people who rent privately are basically split, and a large plurality of owner occupiers are opposed.

The fact that Inner London has a higher proportion of low income and/or renting households probably goes a long way to explaining why it has the highest support for new supply in the country. The tenure comparison also supports the case for an economic rationale behind attitudes to new supply. Owner occupiers would tend to have the least need for new supply and the most to lose if new supply brings down house prices, while social housing tenants have little incentive to worry about lower local prices and are more likely to know someone who needs a home or be in need of one themselves. And perhaps private renters are somewhere in the middle.

As a final point, I'd just like to emphasise that we tend to think of attitudes to new housing supply as a personal matter, but it has potentially huge implications for the lives of other people. If we succesfully oppose new housing supply in our local area we make it more difficult for people to find a decent, affordable place to live. We may not ever meet those people or even be aware of their existence, but they exist alright. This is in large part a moral issue, and I think we should be willing to discuss our attitudes to it in terms of their moral consequences.

Friday, 1 July 2011

Cycling journey times are very reliable

A couple of sources on cycle journey time reliability. First there's TfL's report of August 2009, which finds (para 10.4) that:

Then there's a survey done by the Chartered Management Institute in 2004, which doesn't appear to be available itself any more but is referenced in a few places, notably this Haringey Council document:

The upshot is that cycling journey times are very reliable, much more reliable than car journeys, because cyclists can usually filter through stationary traffic. This implies that if more people switched from cars to bikes then overall journey time reliability would go up, all else equal. But if your main measure of journey time reliability excludes cyclists and focuses only on motor vehicle traffic, as TfL's does, then the risk is that your attempts to improve reliability for motor vehicles will come at the expense of a mode which will always be much more reliable.

journey times are very consistent per rider, and far more independent of traffic conditions than [for] larger vehicles such as cars. Cyclists do not travel in the main traffic stream and therefore avoid the main barriers (barring signals) that other road users face

Then there's a survey done by the Chartered Management Institute in 2004, which doesn't appear to be available itself any more but is referenced in a few places, notably this Haringey Council document:

According to a Chartered Management Institute survey (2004) of 4,000 of their members, cyclists are more likely to arrive at work on time, and are more productive and less prone to stress than their counterparts arriving by car or public transport. The Institute found that 58% of cyclists say they are never disrupted by traffic, compared to only four per cent of drivers. Nine per cent of cyclists say they are stressed by their journey to work, compared to nearly 40% of drivers; almost a quarter of motorists feel their productivity is affected by the stress of their commute, compared to zero percent of the cyclists.

The upshot is that cycling journey times are very reliable, much more reliable than car journeys, because cyclists can usually filter through stationary traffic. This implies that if more people switched from cars to bikes then overall journey time reliability would go up, all else equal. But if your main measure of journey time reliability excludes cyclists and focuses only on motor vehicle traffic, as TfL's does, then the risk is that your attempts to improve reliability for motor vehicles will come at the expense of a mode which will always be much more reliable.

"Exponentially diminishing collective returns"

The New York Times is hosting a discussion on the somewhat over-hyped distinction it has drawn between European cities supposedly out to make motorists' lives a misery and American cities which are not. I like Tom Vanderbilt's contribution best, as I think it puts the idea that cities should be remade around cars in its proper historical place:

I love that phrase - exponentially diminishing collective returns!

The idea that a city like New York could be made wholly compatible with the car looks increasingly antique, a paved-with-good-intentions fever dream now as obsolete as the idea of tower-block housing projects. As Michael Frumin, a transportation expert, once observed, if the morning subway commute were to be conducted by car, we would need 84 Queens Midtown Tunnels, 76 Brooklyn Bridges or 200 Fifth Avenues.

The car, with its exponentially diminishing collective returns — for example, traffic — is not the solution to mobility in the increasingly crowded cities of the 21st century. The sooner we put this flat-earth belief behind us, the faster we can get along with ideas for more efficient forms of mobility.

I love that phrase - exponentially diminishing collective returns!

Monday, 27 June 2011

NBER papers on transport and labour economics

The NBER publish some good economics! Here are a couple of new working papers I liked the sound of :

(See also my post on external accident risk)

In other words, policies that protect against unemployment and poverty also reduce mobility, which obviously doesn't mean the policies aren't worthwhile but does tend to increase the likelihood of both spatially concentrated and temporally extended unemployment.

Pounds that Kill: The External Costs of Vehicle Weight

Michael Anderson, Maximilian Auffhammer

Heavier vehicles are safer for their own occupants but more hazardous for the occupants of other vehicles. In this paper we estimate the increased probability of fatalities from being hit by a heavier vehicle in a collision. We show that, controlling for own-vehicle weight, being hit by a vehicle that is 1,000 pounds heavier results in a 47% increase in the baseline fatality probability. Estimation results further suggest that the fatality risk is even higher if the striking vehicle is a light truck (SUV, pickup truck, or minivan). We calculate that the value of the external risk generated by the gain in fleet weight since 1989 is approximately 27 cents per gallon of gasoline. We further calculate that the total fatality externality is roughly equivalent to a gas tax of $1.08 per gallon. We consider two policy options for internalizing this external cost: a gas tax and an optimal weight varying mileage tax. Comparing these options, we find that the cost is similar for most vehicles.

(See also my post on external accident risk)

The Incidence of Local Labor Demand Shocks

Matthew J. Notowidigdo

Low-skill workers are comparatively immobile: when labor demand slumps in a city, low-skill workers are disproportionately likely to remain to face declining wages and employment. This paper estimates the extent to which (falling) housing prices and (rising) social transfers can account for this fact using a spatial equilibrium model. Nonlinear reduced form estimates of the model using U.S. Census data document that positive labor demand shocks increase population more than negative shocks reduce population, this asymmetry is larger for low-skill workers, and such an asymmetry is absent for wages, housing values, and rental prices. GMM estimates of the full model suggest that the comparative immobility of low-skill workers is not due to higher mobility costs per se, but rather a lower incidence of adverse labor demand shocks.

In other words, policies that protect against unemployment and poverty also reduce mobility, which obviously doesn't mean the policies aren't worthwhile but does tend to increase the likelihood of both spatially concentrated and temporally extended unemployment.

Sunday, 26 June 2011

Nicer inner cities might be a mixed blessing for people on low incomes

Ben Rogers, writing in the Standard, gets to the heart of dilemmas around aspirations towards 'mixed communities' in the face of economic forces that seem to be acting against them. Read the whole thing, but here is an extract:

The evidence on the impacts of mixed communities is indeed fairly mixed, and the point about costs is an important one, but I'm not sure it's the whole story. If the cheaper areas of the future are going to be in the suburbs then the cost of transport for the poor to get to city centre jobs is going to be higher. School quality and environmental amenity are also likely to be lower in cheaper areas - that's part of the reason why they're cheaper, after all.

So I think the benefits to the poor of being 'squeezed out' of affluent city centres are still fairly ambiguous, even leaving aside the very large transitional costs facing anyone who does make such a move (as demonstrated by the fact that the people affected by the cuts to housing benefit generally seem pretty unhappy about it).

More broadly I think these dilemmas highlight a very important shift in how our cities function. To simplify massively, in the past when cities had lots of dirty industry they had dirty environments as a result, particularly towards the centre. That encouraged richer people to move out of inner cities as soon as they could afford to and transport allowed. On the other hand, poorer people could save on transport costs by living in the centre, close to the jobs but also close to the pollution.

But over time, as incomes rose and as environmental regulation strengthened, cities lost most of their dirty industry (and associated crime, perhaps). Inner city environments improved drastically, which meant that the rich have started to come back in, lowering their transport costs at the same time. That pushes up housing costs in the centre. So the poor have to choose between staying put and paying higher housing costs, or moving out and paying higher transport costs. That's if the poor rent in the private sector, anyway. If they own their own place or live in social housing, they get to benefit from an improved inner city environment without higher housing costs. So there's an argument that inner city social housing is of increasing benefit to the poor as city centre environments improve. You can also see why it's of increasing interest to those who think we should sell it off.

Obviously that's a very broad sketch with quite a few simplifications and assumptions thrown in[1]. But I think the link between 'greener cities' and displacement of the poor is real enough.

[1] E.g. it assumes that the centre still has the lion's share of the jobs, which is the case in many European cities but not in some US ones.

As property prices go up, lower earners will be squeezed out. In the absence of a massive house-building programme in central London, the capital will become to feel more like Paris, with a rich centre and a poorer outer-ring. Rent policy can slow or hasten this process but not reverse it.

Should we care? Instinctively I want to answer "yes". I look on with misgivings as the Highbury street on which I live becomes steadily fancier - even though I know that I have contributed to that process and stand to gain from it financially.

It has been an article of faith among socially-minded reformers since the days of Joseph Rowntree and Ebenezer Howard that "mixed communities" are a good thing and income segregation bad. Yet the evidence in favour of mixed-income neighbourhoods is weak. Poor children from rich neighbourhoods do not seem to do any better in life than those from poor neighbourhoods. LSE economists Paul Cheshire and Henry Overman argue that there might even be benefits for poor people living in poor neighbourhoods: shops are cheaper and public services tailored to them.

The evidence on the impacts of mixed communities is indeed fairly mixed, and the point about costs is an important one, but I'm not sure it's the whole story. If the cheaper areas of the future are going to be in the suburbs then the cost of transport for the poor to get to city centre jobs is going to be higher. School quality and environmental amenity are also likely to be lower in cheaper areas - that's part of the reason why they're cheaper, after all.

So I think the benefits to the poor of being 'squeezed out' of affluent city centres are still fairly ambiguous, even leaving aside the very large transitional costs facing anyone who does make such a move (as demonstrated by the fact that the people affected by the cuts to housing benefit generally seem pretty unhappy about it).

More broadly I think these dilemmas highlight a very important shift in how our cities function. To simplify massively, in the past when cities had lots of dirty industry they had dirty environments as a result, particularly towards the centre. That encouraged richer people to move out of inner cities as soon as they could afford to and transport allowed. On the other hand, poorer people could save on transport costs by living in the centre, close to the jobs but also close to the pollution.

But over time, as incomes rose and as environmental regulation strengthened, cities lost most of their dirty industry (and associated crime, perhaps). Inner city environments improved drastically, which meant that the rich have started to come back in, lowering their transport costs at the same time. That pushes up housing costs in the centre. So the poor have to choose between staying put and paying higher housing costs, or moving out and paying higher transport costs. That's if the poor rent in the private sector, anyway. If they own their own place or live in social housing, they get to benefit from an improved inner city environment without higher housing costs. So there's an argument that inner city social housing is of increasing benefit to the poor as city centre environments improve. You can also see why it's of increasing interest to those who think we should sell it off.

Obviously that's a very broad sketch with quite a few simplifications and assumptions thrown in[1]. But I think the link between 'greener cities' and displacement of the poor is real enough.

[1] E.g. it assumes that the centre still has the lion's share of the jobs, which is the case in many European cities but not in some US ones.

Thursday, 23 June 2011

Affordability or amenity?

Rowan Moore reads the new enormobook 'Living in the Endless City' and fishes out a good quote:

Over the past few decades city centres in richer countries have generally become better places to live, as crime has fallen and dirty industries are either priced or regulated out [1]. So demand to live in city centres has also gone up. Faced with higher demand, cities can choose to increase supply (by building more housing and offices) or to keep things as they are.

If you increase supply you are changing the environment that people have come to value. People being risk-averse, it's not surprising that they tend to resist. But not increasing supply (or, more commonly, not increasing it enough to match rising demand) means that over time, improved quality of life feeds into higher prices for housing and commercial space. Which is exactly what we have seen happen in Manhattan, and what I think is happening in London.

So cities with improving environments have a decision to make: if they try to keep their city affordable, they need to make some big changes to its built environment just as people start attaching a greater value to the status quo. Economists sometimes act like this is a no-brainer, but it really isn't. I think that people become more resistant to change in the built environment (i.e. to new housing or office supply) as its amenity value increases, and you can see why. But the implications for the long-term affordability of city centres are very serious.

[1] These two trends are two sides of the same coin, if you buy the argument that falling lead pollution caused falling crime rates - and I think I do.

Suketu Mehta, on Mumbai, articulates the fundamental dilemma of urban improvement. No matter how appalling the overcrowding and squalor might seem, the city will continue to attract yet more people because it still offers things, such as freedoms and opportunities, that the countryside cannot. And, therefore, according to a planner quoted by Mehta, "the nicer you make the city, the larger the number of people that will come to live there".Now, on the one hand, that's extremely obvious. But on the other hand I'm not sure we always think through the implications.

Over the past few decades city centres in richer countries have generally become better places to live, as crime has fallen and dirty industries are either priced or regulated out [1]. So demand to live in city centres has also gone up. Faced with higher demand, cities can choose to increase supply (by building more housing and offices) or to keep things as they are.

If you increase supply you are changing the environment that people have come to value. People being risk-averse, it's not surprising that they tend to resist. But not increasing supply (or, more commonly, not increasing it enough to match rising demand) means that over time, improved quality of life feeds into higher prices for housing and commercial space. Which is exactly what we have seen happen in Manhattan, and what I think is happening in London.

So cities with improving environments have a decision to make: if they try to keep their city affordable, they need to make some big changes to its built environment just as people start attaching a greater value to the status quo. Economists sometimes act like this is a no-brainer, but it really isn't. I think that people become more resistant to change in the built environment (i.e. to new housing or office supply) as its amenity value increases, and you can see why. But the implications for the long-term affordability of city centres are very serious.

[1] These two trends are two sides of the same coin, if you buy the argument that falling lead pollution caused falling crime rates - and I think I do.

Labels:

cities,

environment,

housing

UK house price to rent ratios aren't all that reliable

The Economist has a nifty interactive resource showing trends in house prices and associated indicators for a bunch of countries. It includes trends in the ratio of house prices to rents, which in theory should be useful as an indicator of over- or under-valuation in house prices - if prices are very high in relation to rents then that's a sign that they are over-valued as an asset in comparison to the income stream they can be expected to earn. According to the Economist's data, the price to rent ratio in Britain is still way above its historical average, and this is evidence that housing is over-valued as an asset.

That could well be true, but I think we should be cautious in how we interpret these figures, because constructing them is not at all straightforward, perhaps particularly in Britain. That's because while we have a bunch of house price indices we have no equivalent for market rents: that is, no reliable and comprehensive data on trends in average market rents, from either official or private sector sources. So what is the Economist using? They say the data is from Office for National Statistics but are no more specific, but since ONS to my knowledge don't have any dedicated market rent data my guess is that they are relying on the 'Rent' component of the official CPI/RPI indices.

The problem with that source is that it includes not just private sector but also social rented housing, i.e. council and housing association stock (see here for the 'basket' of goods and services included in CPI/RPI). But social housing rents are strictly controlled by government regulation, so the trend in social rents is typically quite different from the trend in market rents, making the CPI/RPI rental index a poor proxy for either.

So I would be much more cautious than the Economist, who confidently assert here that British house prices are 30% over-valued and do the same calculation for a bunch of other countries, the data for which may or may not be any better than for Britain. The benchmark used to identify over- or under-valuation is a long-run average, but even leaving aside the very large problem of data quality it is not clear to me that the level of the price/rents ratio in, say, the late 1970s is a good guide to what it should be in the 2010s.

Anyway, there you have it. Note that I'm not saying British houses aren't over-valued, just that you can't really tell from the market rents data we have at the moment. I have heard that the Valuation Office Agency will start publishing statistics based on their very extensive market rents database soon, which would be great, but that still won't provide the kind of historic trend the Economist's table requires.

That could well be true, but I think we should be cautious in how we interpret these figures, because constructing them is not at all straightforward, perhaps particularly in Britain. That's because while we have a bunch of house price indices we have no equivalent for market rents: that is, no reliable and comprehensive data on trends in average market rents, from either official or private sector sources. So what is the Economist using? They say the data is from Office for National Statistics but are no more specific, but since ONS to my knowledge don't have any dedicated market rent data my guess is that they are relying on the 'Rent' component of the official CPI/RPI indices.

The problem with that source is that it includes not just private sector but also social rented housing, i.e. council and housing association stock (see here for the 'basket' of goods and services included in CPI/RPI). But social housing rents are strictly controlled by government regulation, so the trend in social rents is typically quite different from the trend in market rents, making the CPI/RPI rental index a poor proxy for either.

So I would be much more cautious than the Economist, who confidently assert here that British house prices are 30% over-valued and do the same calculation for a bunch of other countries, the data for which may or may not be any better than for Britain. The benchmark used to identify over- or under-valuation is a long-run average, but even leaving aside the very large problem of data quality it is not clear to me that the level of the price/rents ratio in, say, the late 1970s is a good guide to what it should be in the 2010s.

Anyway, there you have it. Note that I'm not saying British houses aren't over-valued, just that you can't really tell from the market rents data we have at the moment. I have heard that the Valuation Office Agency will start publishing statistics based on their very extensive market rents database soon, which would be great, but that still won't provide the kind of historic trend the Economist's table requires.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)