Cyclists make these kinds of calculation all the time. They take quiet back streets to avoid dangerous main roads, they dismount and cross at pedestrian signals rather than try to turn right across moving traffic, and so on. There are a number of daredevils who take the most direct route to where they're going regardless of the conditions, but in my experience almost everyone who cycles accepts some kind of delay or diversion in exchange for extra safety, comfort or peace of mind.

But that's just the people who cycle, and in Britain they are relatively few in number. Most people don't cycle, presumably because they don't think it worth their while. On the face of it this is a puzzle, since cycling can be faster than driving or other modes of transport in many contexts. But the reality is that this speed advantage can be wiped out if you have to make too many of these delays and diversions to make the trip acceptable by bike. If people have to go around the houses to feel safe on a bike, many of them will just take the car instead.

The flip-side is that if we can make the quick and direct routes safe and comfortable to cycle, then many people will find that cycling suddenly makese sense for them. This is what happens in the Netherlands, where people are not expected to either brave unpleasant conditions on main roads or work out a convoluted but quiet route on back roads. By making cycling safer, they have made it quicker too, and that's the key.

Evidence on how far people will go out of their way to avoid unpleasant or dangerous roads has long been one of the missing pieces in understanding the choice of whether or not to cycle. If we knew how much time people would give up to avoid a bad junction, we can guess how much time we could save them by making it safe and pleasant to cycle through, and then estimate the impact on cycling's local mode share, traffic congestion and so on. These factors are key to the kind of economic analysis which determines how transport funding gets spent and which has so far more or less ignored cycling.

So this research into cyclists' route choices carried out for TfL by Steer Davies Gleave could be very important, because it tries to answer exactly these questions. They asked people (mostly people who cycle in London) to rate the attractiveness of different types of junction types and cycling conditions, and crucially it asks them how much time they would be willing to add to their journey to avoid particular situations.

Here are some of the results. First, the extent to which people agreed with various statements about route choice, by their frequency of cycling, age and gender.

The first thing to note is how many people, even frequent cyclists, agree with statements like "If I had to negotiate a number of difficult junctions I would try to find another route" and "I would prefer cycling in a cycle lane which is separate from the traffic even if it meant a longer journey". But the different average responses by gender are striking too: women seem significantly more likely to change their routes due to safety concerns than men, consistent with findings from the British Social Attitudes survey showing women are more likely to think the roads are too dangerous to cycle. Finally, long-term cyclists (those with more than two years experience) are consistently more willing to endure bad conditions in exchange for a quicker journey than inexperienced ones. There is probably a learning or hardening effect here, with people becoming more skilled or better able to cope with unpleasant conditions over time - but there is undoubtedly a selection effect too, with many people trying out cycling but not keeping it up due to safety issues. Experienced cyclists constitute the small minority of people who are willing and able to deal with the problems posed by cycling on British roads.

The researchers also asked people to rate how safe they felt cycling through different types of junctions.

Here, the striking thing is how unsafe people (mostly cyclists, bear in mind) think fairly common junction types are. The very first junction in my five-mile commute to work is a right turn from a side road onto a main road, and it's not very nice: I have to wait for a suitable gap in the streams of traffic and then dart into it at a decent speed. Clearly for many people this would be one junction too far and the journey as a whole would be unviable by bike.

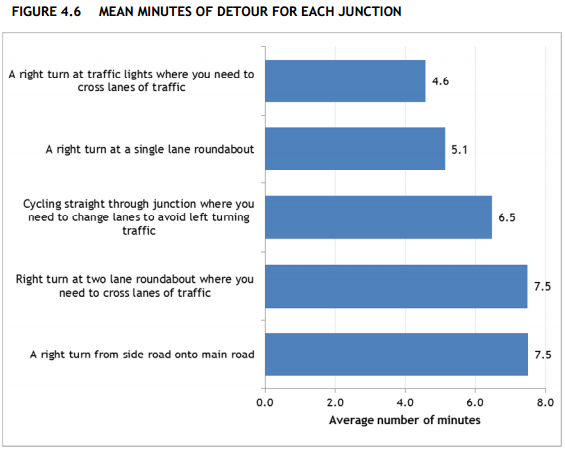

The next charts illustrate how important this all is.

A majority of people said they were willing to accept a detour of over five minutes to avoid a right turn at a two-lane roundabout, or a right turn from a side road to a main road. The average was 7.5 minutes. These are very big figures, surprisingly big to me at first - but I'm an experienced, battle hardened cyclist, and as I said at the start I still make detours, though maybe not as big.

It's worth emphasising again that these kinds of results go a long way towards explaining why more people don't cycle in Britain. It's because our main roads are so dangerous and unpleasant to cycle on that people would rather sacrifice huge chunks of time than do so, to the extent that cycling is for most purposes no longer worthwhile.

Finally, the researchers asked people to compare different types of cycling facility. The chart below shows the average benefits people ascribed to each type of facility, with the most popular (off-road routes) set at 100.

The key result here is that there is a big preference for off-road cycling infrastructure as compared to bus lanes, advisory cycle lanes or mandatory cycle lanes, particularly among women. In comparison, the type of road doesn't seem to matter very much.

This certainly looks like a big win for segregated bike lanes (consistent with lots of other evidence on the subject), but it's worth bearing in mind that the picture of an 'off-road' route people were prompted with (below) looks more like a route through a park than a typical segregated track alongside a main road, and that has probably affected the results somewhat.

This is very valuable research because it starts to quantify the extent to which our current road designs fail people and prevent cycling from becoming a mainstream choice, and because it can also help us quantify the benefits of better infrastructure. It deserves to be read widely, by both campaigners and planners.

Thank you for bringing this research to my attention, which I am sure would otherwise have passed me by.

ReplyDeleteI think the point needs to be emphatically made that this was primarily a survey of existing cyclists, with 81% of the respondents cycling at least twice a week, 71% having cycled in London for at least a year, and 69% feeling confident enough to cycle on any kind of road.

Even so, it is noteworthy, as you point out, "how many people, even frequent cyclists, agree with statements like 'If I had to negotiate a number of difficult junctions I would try to find another route' and 'I would prefer cycling in a cycle lane which is separate from the traffic even if it meant a longer journey'".

The effect of parks and green spaces was significant, with around half saying they would change their route in order to be able to use such off-road facilities.

One thing that struck me was that, even though residential streets are currently not very well-suited to travel by bike (as a rule of thumb), they were still preferred to other road types. This is consistent with evidence from the Netherlands (here), which says: "Cyclists often prefer a quiet residential street to an autonomous bicycle path alongside busy traffic arteries."

I was intrigued by the response to the question: "The quality of signage and cycle markings has no influence on what route I take."

On what route I would take, or on what route I currently take? If most people are going to stick to the routes they know, regardless, then I suppose it doesn't make any difference.

Finally, if this survey was ever repeated, I would be interested to know how people felt about a right-turn from a main road onto a back street (as here).

Thanks again.

Cyclists in NL prefer a quiet residential street to a path alongside busy traffic arteries for a different reason than their GB counterparts.

ReplyDeleteIn NL the choice will be motivated by comfort: QUIET street vs path alongside busy (noisy, smelly) road. Both roads will be taken by all ages and gender without real problems, but comfort makes a preference. Like a luxury choice. The time people want to spend not riding along the busy road will be much less than these GB numbers (though I do not know of any research in NL in this matter), from what I hear from my fellow fietsers (NOT cyclists)

In GB I guess the choice will be motivated by safety (survival instinct), which I would consider a real problem. So the time lags people are willing to take to evade some situations, sound pretty extreme to my dutch ears. I do not know of any NL people giving the same sounds. We're just spoiled, clearly.

No, I think cyclists in GB prefer residential streets for the same reason, but the point you make in your very last sentence is well understood: even in Copenhagen - Steffen Rasmussen told a GLA committee hearing - there are certain junctions which some cyclists are known to avoid.

ReplyDeleteIf you have never cycled in London, it's difficult to explain how things still are, and how far we've still got to go. Sad to say, but the moral of this children's TV programme from the early 1970s would not be entirely out of place in this day and age.

The case is, it's actually very difficult to use the back streets, what with all the one-ways and the lack of good signage and what-not. If you don't have the confidence to cycle on a main road, then almost certainly you won't be using a bicycle for utility purposes.

In a recent comment on the Cyclists in the City blog, I wrote that the cycle networks in the Netherlands are developed around a combination of main road routes (treated) and back street routes (traffic-calmed). "So it's not a case of one or the other, but a combination of the both, and then let users decide which route suits them best."

In London, cyclists effectively have "no choice other than to cycle through ridiculously designed road junctions", whereas in the Netherlands, they have two choices: they can either avoid the junction altogether, or they can cycle through the junction using well-designed facilities.

It's going to take quite a long time for us to get to this point. We don't even have a functioning cycle network!

Thank you for a very interesting and well presented article.

ReplyDeleteI am interested that going 'straight on where you need to change lanes to avoid left turning traffic', is a similar level of threat to turning right at multi lane roundabout. This concern needs to be addressed more in cycling design standards. I will re-look again.

Also, I note the strong agreement to preferring

- cycling in a separate cycle lane

- try to avoid cycling with fast flowing traffic

- cycle in a road with less traffic

Does this mean the London Cycling Design Standards (LCDS) have got it right? Where they note cycle lanes or tracks should be provided to assist cyclists where motor vehicle flows and/or speeds are medium or high (30+mph). So in a post 20mph environments, cycle lanes may become rare, unless the traffic volume is VPD is 3000 - 8000VPD 300-800VPH (medium), or 8000 - 10000VPD, 800-1000VPH (higher), or greater.

And they provide a “target for quiet cycle routes along back streets, residential roads and roads through parks should be flows below 1500 veh/24hours and speeds below 20mph”

But… what I feel Boroughs are following is the guidance from ‘Manual For Streets’ there is an emphasis where ‘cyclists should be catered for on the road if at all practicable’

6.4.5 Cyclists are particularly sensitive to

traffic conditions. High speeds or high volumes

of traffic tend to discourage cycling. If traffic

conditions are inappropriate for on-street

cycling, the factors contributing to them need to

be addressed, if practicable, to make on-street

cycling satisfactory. This is described in more

detail in Chapter 7.

6.4.8 Cyclists should be catered for on the

road if at all practicable. If cycle lanes are

installed, measures should be taken to prevent

them from being blocked by parked vehicles.

If cycle tracks are provided, they should be

physically segregated from footways/footpaths

if there is sufficient width available. However,

there is generally little point in segregating a

combined width of about 3.3 m or less. The

fear of being struck by cyclists is a significant

concern for many disabled people. Access

officers and consultation groups should be

involved in the decision-making process.

Seems a disconnect here in UK design standards and cyclist's preference for safer accessibility for their routes or junction safety concerns.

Looking at the list of junction types to avoid, it also makes a difference to me if I know I'm going to end up with an uphill start. Right turn from a minor to major becomes a right pain and even straight through lights can be awkward, with traffic trying to pull past me before I'm in the pedals

ReplyDelete